by Maxime Gauin

Blue and Yellow David Star: anti-Semitism, anti-Ukrainianism and their convergence, from the Soviet Union to today’s Russia

Even before the invasions of 2014 and 2022, the Putin regime had launched a disinformation warfare in America and Europe, trying to deny the importance of Soviet legacy, Soviet reflexes and Soviet mentality in Moscow. Naturally, this warfare increased after the illegal annexation of Crimea (2014), the invasion of the Donbas the same year, and the general invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The aim of this article is to contribute to defend the truth against such a propaganda. First, it recalls the rise of anti-Semitism in the USSR, which became a priority for the Kremlin during the last decades. Then, it emphasizes the particular hostility of the Soviet regime against any Ukrainian national feeling. The third part studies a largely neglected aspect: How hostility towards the Jews and the non-Russified Ukrainians converged in the Soviet propaganda of the 1970s, with authors sometimes active as late as 2010s. The fourth and last part exposes the legacy of that Soviet convergence in the Putinist policies today, and how a certain number of Westerner spread hatred against both Jews and Ukrainians.

This is not a short article, but it cannot be so.

Soviet anti-Semitism: From popular hatred to state policy

The Soviet top leaders of the first years, except Stalin, were devoid of anti-Semitic prejudice. Lev (Leon) Trotski, Lev Kamenev and Grigori Zinoviev were born in Jewish families; Lenin constantly rejected anti-Jewish feelings. Regardless, Lenin and even more Trotsky refused to repress the elements of the Red Army who committed pogroms during the civil war, considering that everyone was needed (we will return later to this issue). There was indeed a clear difference between most of the top leaders on one side, a significant part of the militant basis on the other side, largely due to the fierce Russian anti-Semitism since in the second half of 18th Century.[i]

The death of Lenin in 1924, and the political defeat of Trotsky, Kamenev and Zinoviev against Stalin in 1926 did not change the Soviet policy immediately. The Soviet state repressed a part of the anti-Semites and Mikhail Kalinin, Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union, publicly deplored in 1926 the rise of the anti-Jewish hatred on the intelligentsia.[ii] But there never was a general repression of the anti-Semites, in this totalitarian state. In mid-1930s, Stalin left unanswered not less than five letters on the persistence of anti-Semitism in the USSR, yet they had been sent by Romain Rolland, a Communist fellow traveller (who broke up with the USSR in 1939) and a very famous writer of the time, sumptuously welcomed as such in Moscow in 1935.[iii]

The situation worsened during the Purges of 1936-1938. During the Kamenev-Zinoviev trial of August 1936, eleven of the defendants (out of sixteen) were of Jewish background.[iv] The persons of Jewish nationality represented 39% of the main officials of the NKVD (later KGB) in 1936, but only 4% in 1939.[v] Three quarters of the clerks arrested in 1938 in Moscow cooperatives were of Jewish nationality[vi] (the USSR counting the Jews like the Russians, the Ukrainians, the Georgians, etc.), a share obviously far superior to their percentage among the clerks working for these cooperatives. Similarly, out of 72 general directors at the Commissariat (Ministry) of Industry sentenced from 1936 to 1938 (most of them to the death penalty, the others to hard labor), 40 were Jewish.[vii] The difference with ulterior periods was: The Jewish nationality of the victims never was emphasized in the official propaganda. But it was suggested by a unofficial voice, Walter Duranty, correspondent of the New York Times in Moscow:

“When you come down to brass tacks, there is no obstacle now to Russo-German friendship, which Bismarck advocated so strongly, save Hitler’s fanatic fury against what he calls ‘Judeo-Bolshevism.’ But Hitler is not immortal and dictators can change their minds and Stalin has shot more Jews in two years of the purge than were ever killed in Germany.”[viii]

Given the close links of Duranty with the Kremlin,[ix] it has been interpreted as a message of Stalin, reiterating his demand for an alliance with Hitler,[x] actually concluded in 1939. Even after the Fürher attacked his ally, in June 1941, Stalin did not change his view of the Jews fundamentally.

In December 1937, the persons of Jewish background represented 4.1% of the USSR Supreme Soviet, but less than 1% in 1946, while the Jewish nationality (it was the Soviet vocabulary) represented 2.1% of the USSR’s population.[xi] A Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was established in Moscow in 1941, but it was merely, in the eyes of Stalin, an instrument among others for his public relations in the U.S. The project of a Black Book on the extermination of the Soviet Jews, which was first suggested by the American interlocutors of the Committee (Albert Einstein, in particular) was seen with suspicion by Stalin, because the idea went from America and because it singularize the Jews, while only the Russians deserved, according to him, a specific emphasis. The publication of the Black Book was blocked in 1946. It was not published in Russian until 1993, and even this first edition was printed in… Lithuania. S. Mikhoels, the best known leader of the Committee, was assassinated in January 1948 in fake accident. The rest of the leadership was arrested in 1949, sentenced to death in 1952 and executed the same year (discreetly, because several defendants refused to “confess” their “crimes,” making impossible a show trial).[xii]

This is true that Stalin supported the establishment of Israel in 1947-1948, but that was by pure calculation: Eliminating the British presence in the Near East and, in the best hypothesis, encouraging Israel to become a neutral state. But Stalin hated the warm welcoming of Golda Meir, the first Israeli ambassador in Moscow, by the Soviet Jews, in 1948. His general paranoia and his anti-Semitism led him to a general attack. By January 1949, the Soviet government and its press launched a campaign of vitriolic articles and, more concretely, of arrests, targeting mostly Jewish artists and intellectuals, in mentioning their original name when they had Russified it, a tactic borrowed from the anti-Semitic elements of the White Russians and the Nazis. The “Zionist plot” was a secondary aspect of the Rajk trial in Budapest, at the end of the same year.[xiii] Quite logically, it comforted David Ben Gourion in his natural inclination: Joining the Western camp. Israel supported the point of view of the NATO members during the Korea War (1950-1953).

In 1951, Stalin severed the military cooperation with Israel and the “Zionist plot” replaced the “Titist plot” as the main pretext for the show trials in the Communist states. Jean-Paul Sartre himself, well-known for his positive view of the USSR until 1956 and of Fidel Castro’s Cuba until 1971, sated to Évidences (the review published in Paris by the American Jewish Committee until 1963): “It is obvious that we are witnessing the emergence of a ‘left-wing’ anti-Semitism” in the Eastern Bloc and particularly Czechoslovakia.[xiv] Actually, the first targets of Stalin were leaders of Czechoslovakia, who had armed Israel, by order of Stalin, in 1947-1948. The defendants were carefully selected: out of fourteen, eleven were “of Jewish origin,” such as Rudolf Slansky, first secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party until his arrest, and the three from Christian background were called “of workers origin.” The ciphering was elementary, if it still existed. Two Israelis were arrested and forced to testify, including Morekhai Oren, a leader of the Mapam, the most Marxist of the Zionist parties and the only one interested (until 1952) in an alliance with the USSR. As usual during the Stalinist years, torture and threats on the closest relatives were used to obtain “confessions” and “testimonies.”[xv] Then, in December 1952, the part of the Eastern Germany leadership who had called anti-Semitism a central element of the Nazi doctrine and advocated the payment of compensations for the Holocaust’s survivors was arrested. MGB (renamed KGB in 1954) officers went to make a census of the Jews, obviously not to make them gifts.[xvi]

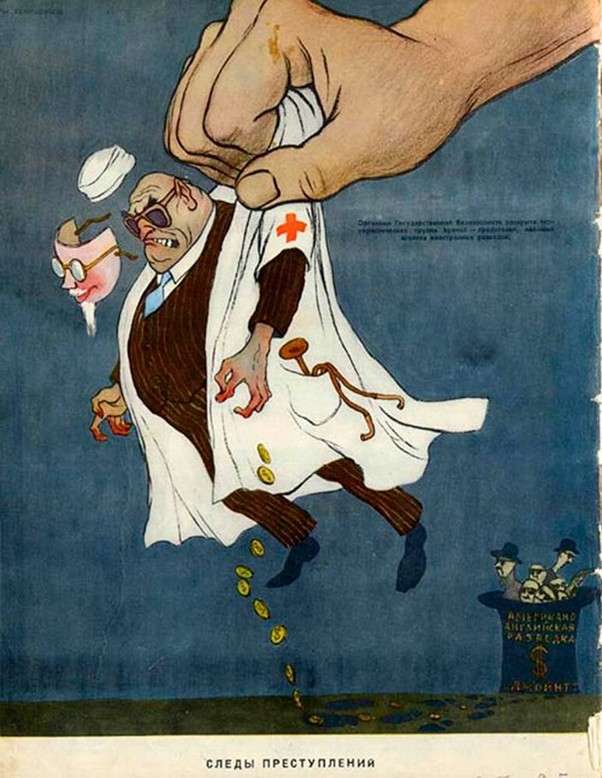

On 1 December 1952, Stalin stated (this was written in the private diary one of his most loyal servants): “Every Jew is a nationalist, an agent of the American secret services.”[xvii] The consequence was the imaginary “Doctors’ plot,” where, one more time, the vast majority of the defendants were of Jewish background (but not all), and which was aimed to prepare a general deportation of the Soviet Jews to Siberia, officially at their own request, to protect them from the popular ire.[xviii] The Slansky trial and the “doctors’ plot” assimilated Zionism and Nazism, but—for instance—the founding father of American neo-Nazism, Francis Parker Yockey understood perfectly what was going on and turned pro-Soviet in 1952, largely by anti-Semitism.[xix] This cartoon, published in the Soviet press in January 1953, is a clear imitation of Nazi ones (the nose, the ears and the fingers of the Jewish doctor are those of racist caricatures, the Jews are associated with money, corruption and hypocrisy):

The death of Stalin stopped the ordeal of the doctors. All the survivors were released in April and rehabilitated. But in Czechoslovakia, Morekhai Oren was sentenced to 15 years in autumn 1953 and several Czechoslovakian to similar sentences in March 1954. All were released in 1956, [xx] as a result of the de-Stalinization organized by Nikita Khrouchtchev. Soviet anti-Semitism did not disappear in 1953 or 1956, but decreased and, at least until 1959, rarely used the anti-Zionist angle,[xxi] in spite of the rapprochement with several Arab dictatorships by 1955, such as Syria, Nasser’s Egypt and the Algerian National Liberation Front.

Everything changed in some years: The removal of Krushtshev in 1964, the subsequent consolidation of the old Stalinist (and fanatically anti-Semitic) Mikhail Souslov, the establishment of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (at the very least with the encouragements of the KGB), the same year, the Six-day war in 1967, the humiliation of Arab nationalism and of Soviet weaponry, the spontaneous rise of anti-Semitism that followed in the Arab world,[xxii] the reinforcement of the American-Israeli alliance in 1968-1970 and the rise, since the Grand Terror of 1937-1938, of intellectually mediocre Soviet leaders, permeable to anti-Semitic prejudices or, at least, seeing anti-Semitism as an efficient tool against the West (against the U.S. above all)[xxiii], all that converged to make the USSR the number one producer of anti-Semitic publications in the world, both for internal and external use.

From 1967 to 1978, not less than 180 anti-Semitic books, often using the anti-Zionist angle, were published in the USSR, including 50 doctoral dissertations, as well as thousands of articles.[xxiv] From 1965 to 1985, at least 230 “anti-Zionist” books were published with state funding in the USSR, cumulating 9 million copies.[xxv] The production peaked in 1982-1985, in the context of the Israeli intervention (against the pro-Soviet groups: PLO, Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, etc.) in the Lebanese civil war, of the culmination of the Cold War (euromissiles’ crisis) and of economic degradation in the USSR[xxvi] and continued until 1987.

Local variant were allowed, if not encouraged, such as the theory of the “Jewish-Masonic plot behind the Committee Union and Progress” (the party in power in the Ottoman Empire from 1908 to 1912, then from 1913 to 1918), a theory very popular among the Armenian nationalists, and reactivated by one of the main leaders of Soviet Armenia, John Kirakosian, in 1982-1983.[xxvii] More concretely, a Tsarist method, the numerus clausus in the universities, was restored in practice in the USSR around 1970, provoking, among others, a collapse of the Soviet research in mathematics in a decade.[xxviii]

Moscow tried to export its propaganda in Western countries as well. For example, in France, the anti-hate speech bill of April 1939 (Marchandeau Act) was rewritten in July 1972 by the Pleven Act. Yet, one of the first persons sentenced by the Paris tribunal as a result of this modification, if not the first, was the editor of a review published by the Soviet embassy in Paris, on 24 April 1973, for having translated two articles initially published in Moscow, plagiarizing a publication of the Tsarist far right (Black Hundreds) dating back 1906, merely replacing “Jews” by “Zionists”.[xxix]

The fear to lose: The rise of Soviet anti-Ukrainianism

Not unlike anti-Semitism, hostility against the Ukrainian culture and national aspirations is largely inherited from the Tsarist period. The Ukrainian language was progressively banned and Ukraine called “Little Russia.” This continuity is equally true for the hostility against the Tatars, the Turkic group who constituted the majority of the population of Crimea until 19th Century. The Stalinist deportation of the Tatars in 1944, which provoked losses representing almost 50% the forcibly displaced persons[xxx] (while there was no logistical problems and no fear to lose the war at that time), did not emerge from nowhere but was a systematization of the Tsarist expulsions and persecutions at the end of 18th Century, namely right after the conquest of 1783, then during and after the Crimea war which opposed France, UK, the Ottoman Empire and Piedmont-Sardinia to Russia. Actually, at least one Tsarist official, Count Nikolai Adlerberg, had advocated a general deportation during the 1850s, and he was prevented from doing so for purely utilitarian reasons, chiefly the economic value of the Tatars as peasants.[xxxi]

The son of a Kalmuk and of an ethnic German, Lenin never was attracted by Grand Russian nationalism and by Russification. Regardless, Ukraine was one of his two top priorities in 1918, because it was the main producer of grain of the ex-Tsarist Empire—and the other one was Azerbaijan, because most of the oil produced in that empire went from Baku. Devoid of ethnic prejudice, he used without hesitation the bloody methods of his emerging totalitarian dictatorship against the Ukrainian (and Azerbaijani) patriots, by December 1917.[xxxii] In spite of the divisions among the Ukrainian patriots, in spite of the concurrence of the anarchist army (you read well) of Nestor Makhno and in spite of the clashes with the White Army of General Anton Denikin (who persistently called Ukraine “Little Russia”),[xxxiii] the Ukrainian national (and anarchist) units continued to fight the Red Army until Autumn 1921,[xxxiv] namely after the Russian-Polish armistice (October 1920) and peace treaty (March 1921), after the suppression of the insurrection in Daghestan (March 1921),[xxxv] after the collapse of the Denikin Army (December 1919-March 1920), of the White Army led by Pyotr Wrangel (November 1920) and of the one of hardcore monarchist Roman von Ungern-Sternberg (summer 1921).[xxxvi] As a late revenge of unity on division, today, the heirs of Makhno proudly identify themselves in the Ukrainian army and fight side by side with all the other fighters, irrespective of their political preferences.

Years of wars (1914-1921) and of plunder by the Bolshevik units (1918-1921), who had been ordered to feed Moscow at any price, provoked the famine of 1921-1922 in Ukraine and other parts of the former Russian Empire. One of the main differences is that Lenin accepted the international aid, mainly the American one, even if the local and the national Soviet authorities welcomed the Americans with a particular reluctance during the first weeks, which prolonged the famine.[xxxvii] However, for a decade, the Ukrainian culture and languages were left free, as long as the writers did not challenge the political monopoly of the Communist Party, in sharp contrast with the Tsarist period. Lenin considered this relative cultural freedom to be the necessary counterpart of the totalitarian dictatorship. Stalin thought otherwise, and acted when he found the time appropriate. A first warning was the famine of 1928-1929,[xxxviii] in a more general context of the Stalinist offensive against the peasantry.

The famine of 1932-1933 was different. It was an offensive against the Ukrainian peasantry in particular, and of an unprecedented scope. It was entirely man made: The harvests of 1932 were sufficient to avoid any shortage; in Belarus and in large parts of Russia, especially near the border, there was no famine (with the exception of the Kuban: See below), yet the Ukrainian peasants who exchanged clothes for food were, every time the GPU (later NKVD, then KGB) caught them, arrested and executed. Similarly, the cities were spared, but the peasants who tried to migrate there were prevented from doing so, except those who were sufficiently lucky for remaining unnoticed. Peasants who tried to steal even a modest quantity of food from the collective farms were summarily executed.[xxxix] The letters of the Communist Ukrainian leadership, who directly accused Moscow to be responsible for the famine (in spite of the obvious risks such a wording represented for their authors) and asking for food supplies were left unanswered by Stalin and Molotov.[xl] The Kuban, located in Soviet Russia but inhabited until the famine by a majority of Ukrainians, suffered the same fate. Stalin was personally warned by members of the Communist Party who naively believed that the famine was due to local tyrants who acted without any instruction from the Kremlin. Naturally, Stalin did nothing[xli] until summer 1933, when he considered the Ukrainian peasantry sufficiently weakened and decimated. As it is well-known, foreign journalists were prevented from coming to Ukraine in 1932-1933,[xlii] Gareth Jones managed to make his job by purely illegal means and later was assassinated in Mongolia by the NKVD for having published the truth in the British and American press.

A letter of Stalin to Lazar Kaganovich, dated 11 August 1932, leaves no doubt on his views and intentions: He does not like the Ukrainian peasantry, his opinion of the Communist Party of Ukraine is hardly better, so the situation must change radically, “otherwise we could lose Ukraine.” This letter is partly rooted in the facts: In March 1930, Ukraine only counted the half of the peasants’ uprisings against the forcible collectivization, and, the same year, the Soviet regime had lost the control of dozens of districts because of such revolts; moreover, the Polish government funded the Prométhée group in Paris, an umbrella organization for Ukrainian, Georgian, Azerbaijani and Central Asian patriots. But Warsaw had signed a non-aggression pact with Moscow in March 1932.[xliii] This is clear that Stalin detested the Ukrainian peasantry for ideological reasons. There was a cultural attachment to private property and individual liberty, much stronger than in the Russian peasantry, and large part of the Ukrainian farmer advocated democratic Socialism, free from state ownership, comparable to the kibbutz—and even more the moshav—in Israel.[xliv] Such an ideological fight was not isolated: At the same time, Stalin had ordered to the German Communist Party to fight the Social-Democrats and to make a tactical alliance with the Nazis. But Stalin’s hostility and paranoia targeted most of the Ukrainians themselves, as he attacked even dedicated Bolsheviks who had followed him until 1931-1932 (italics added):

“Thousands of Ukrainian communists and intellectuals are arrested in 1933. Skrypnik, an old member of the Central Committee, October [1917] fighter, Stalinist from the outset, People’s Commissar of Education in the Kharkov Cabinet, blows his brains out so as not to see several of his protégés shot. Shumsky, leader of the Ukrainian Communists, is sent to the Solovietsky Islands.”[xlv]

In his report of February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev vividly denounced the purges inside the Party, and a part of the persecutions against whole nations, but he remained silent on the famine of 1932-1933 and he never rehabilitated the Crimean Tatars. The fact that he was a Soviet leader in Ukraine during the 1930s has surely something to do with these choices, but this is not necessarily the sole reason. Crimea was and remains a strategic region for Moscow. The very idea of a collective punishment against Ukrainian peasantry was not something unpopular in the USSR Communist party, even if many considered the Stalinist practices excessive, especially in 1932-1933.

Indeed, Ukraine was the second vastest Soviet Republic and also the second by its population. Its agricultural lands were the richest of the USSR. About one third of the military industrial basis of the USSR was located in Ukraine. The R-36, an intercontinental nuclear, was designed by Ukrainian engineers during the 1960s. Another reason is the rare continuity of armed opposition to the Soviet power and the particular place of these fighters in the memory of the Soviet leadership. The fights of 1918-1921 and the uprisings of 1930 have been already evoked, but the most durable one is posterior. After having killed or wounded about 17,000 German soldiers from February 1943 to autumn 1944, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) fought the Red Army for a decade. According to the NKVD, 87,571 operations were conducted against the UPA from 1944 to 1946 only. In spite of the assassination of its chief in 1950, UPA units continued to pose severe problems to the Soviets until 1954, a last outbreak occurred in 1956-1957[xlvi] and the very last unit was destroyed in 1960. Certainly, unlike the men of Petliura, the UPA did not suffer of divisions, but the supplies from the Western powers were largely sabotaged by the betrayal of Kim Philby. Only the Lithuanian (1944-1953), Estonian (idem) and Latvian (1944-1957) guerrillas can be compared to the UPA, and the Baltic States have neither the size nor the rebellious past of Ukraine.

It is also remarkable that the GPU (ancestor of the KGB) assassinated S. Petliura in 1926,[xlvii] namely years after the final defeat of his units, and that the KGB assassinated Stepan Bandera (chief of the OUN-B, the political wing of the UPA) in Munich 1959, when the UPA had almost disappeared. They were still feared after the defeat on the battlefield. The only logical explanation is: The Kremlin was concerned about a revival in both cases. After a parenthesis, hostility to Ukrainian national identity re-emerged in the 1970s, but this time, it was often mixed with anti-Semitism.

Convergence of hatreds

During the 1960s, as a result of the de-Stalinization, perhaps also due to a short-term relief provoked by the assassination of Bandera, followed by the elimination of the last guerrilla unit in Soviet Ukraine, Ukrainian culture was tolerated again by the Soviet censorship. Petro Shelest, who incarnated this return to the Leninist practices (relative cultural liberty to make acceptable the Soviet dictatorship), was the main leader of Soviet Ukraine from 1961 to 1972 and even entered the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet in 1966, but he was removed because of his “national deviations” and “national narrow-mindedness”. His supporters in the Communist Party of Ukraine were removed, too, and Ukrainian intellectuals were arrested, first in 1972, then after 1975 and the establishment of an Helsinki Committee in Ukraine, named after the Helsinki Final Act, co-signed in 1975 by the USSR and all the European states (except Albania, which signed after the collapse of the Communist regime).[xlviii] The Helsinki Final includes the civic and cultural rights, something Moscow had no intent to respect.

This is this decade of limited and politically controlled cultural revival, and a not a surge of “Ukrainian nationalism” abroad, that explains the vitriolic publications analysed below. Indeed, the 1970s are probably the less active decade of Ukrainian patriotism in the diaspora.[xlix] The 1950s, 1960s[l] and 1980s[li] were marked by much more publications by Ukrainians and their friends on the sensitive topics.

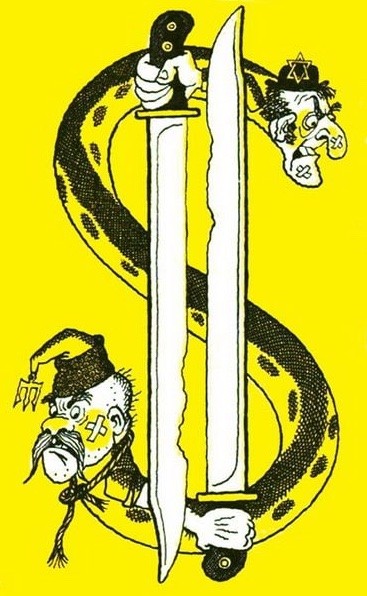

One of the most striking Soviet caricatures combining anti-Semitism and hatred of Ukrainian national feeling, during the 1970s, is this one:

The de-humanization by the assimilation to a snake is a classic of anti-Semitic iconography since late 19th Century, like the big nose of the Jewish face. The assimilation of the Jews to American finance (here, the dollar) is another classic. What is more original hear is the strict equivalence between “Zionism” and Ukrainian patriotism, as dangers on equal terms for the USSR.

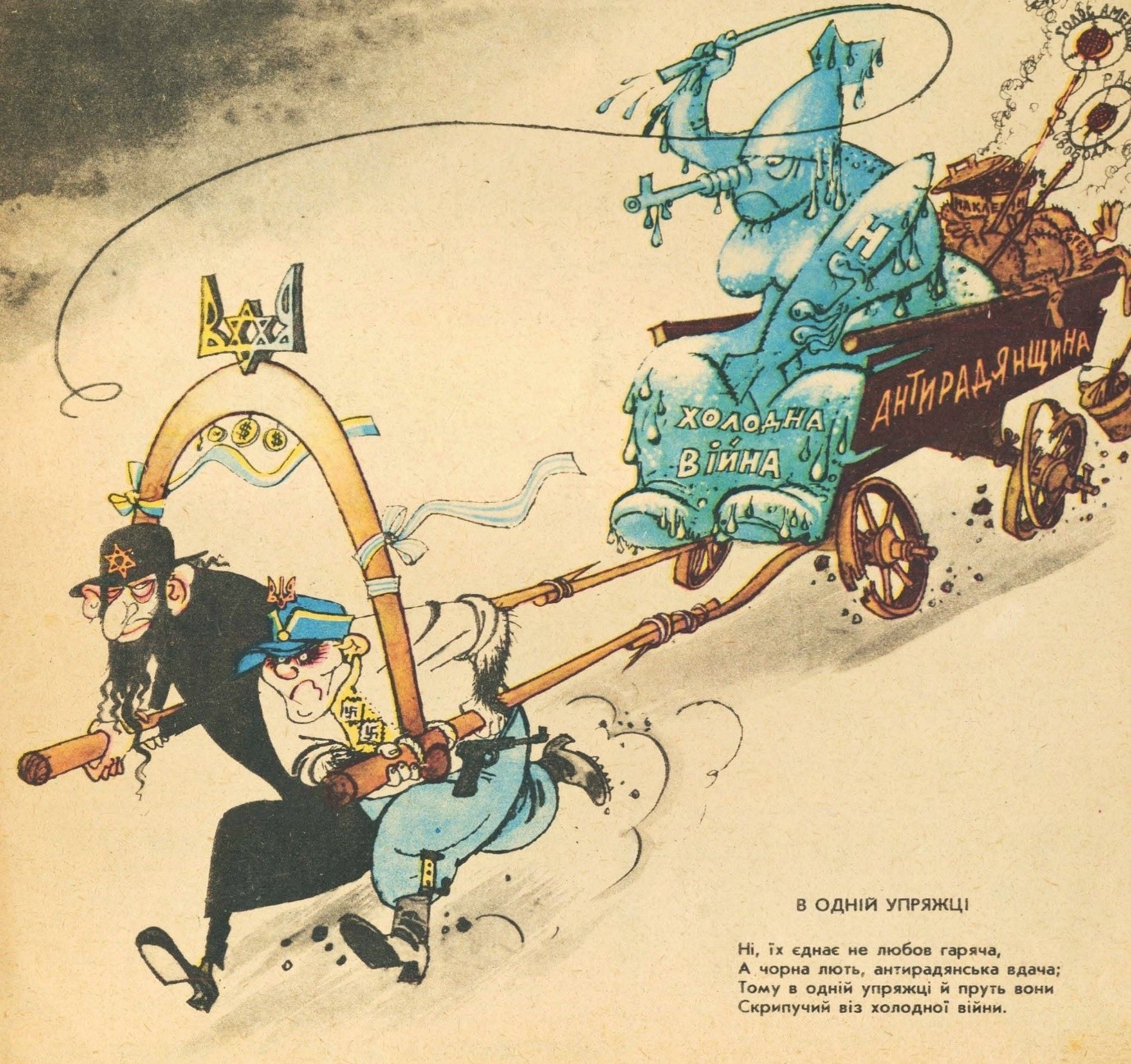

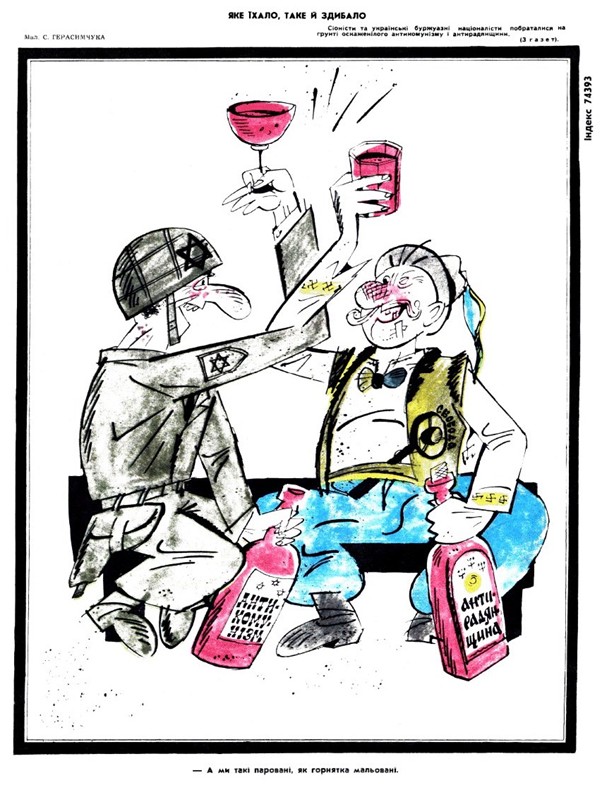

Another clear example is this one:

Ukrainian patriotism and “Zionism” (represented with the codes of racial anti-Semitism: Nose, ears and hands) are, once again, presented as the two main auxiliaries of the USA; “they are in the same team.” The merging of the Ukrainian trident and of the David star, on the top, the use of the Ukrainian colors (blue and yellow) next to the “Zionist” character and of the Israeli colors (blue and white) next to the Ukrainian character only confirm the strict equivalence implied between the two enemies of Moscow. The H bomb is an accusatory reversal, given the context of the Euromissile crisis, provoked in 1977 by the USSR.

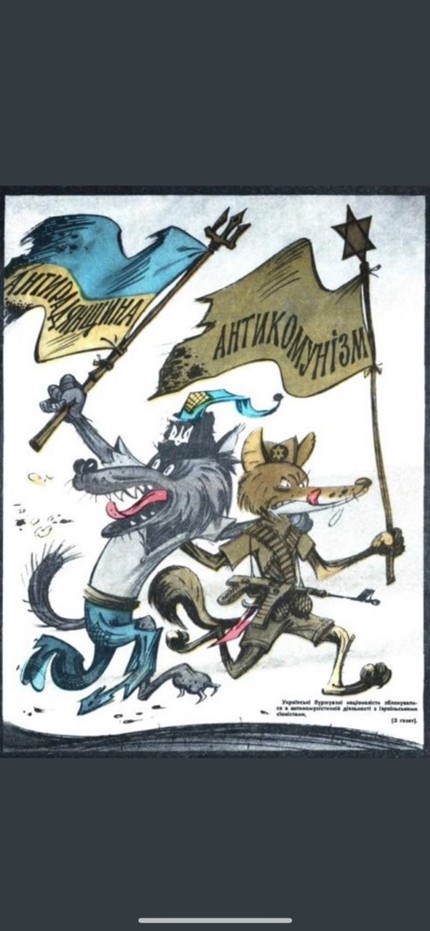

This other caricature does not use the code of racial anti-Semitism but the explicit conclusion is the same:

The text reads: “The wolf and the fox are different but they behave the same — Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists have joined forces with Israeli Zionists in their combined efforts to counter communism.”

And this is same for this one:

Yet, this obsessive assimilation was not limited to “satire”. The clearest example is a short book entitled Anti-Sovietism—Profession of Zionists, published in at least three languages (Russian, English and French) in 1972. It was initially (1971) a series of articles published by the Pravda, the most important daily of the USSR, and these articles were found significant enough to be commented at the front page of the New York Times. The author, Vladimir Bolshakov, was one of the main redactors of the Pravda (the main Soviet daily) for the international affairs, and he was specialized in anti-Semitic attacks form the anti-Zionist angle. He even was the review reader of a short book alleging that the Zionists control the Western military-industrial complex; the text was illustrated with a David star in the middle of a spider web, an image commonly used by the Nazi newspapers such as Der Stürmer. Bolshakov’s 1972 book was published by the Novosti press agency, active in 110 countries and established with the support of the KGB. Novosti played a key role in the publication of “anti-Zionist” books and booklets from 1970 to 1987.[lii]

In his book of 1971, Vladimir Bolshakov uses the traditional Soviet arguments against Israel, and more recent ones, such as the “Zionist” preponderance in the Czechoslovakian media during the Prague spring (January-August 1968),[liii] an attempt to establish “Socialism with a human face,” brutally terminated by a Soviet invasion. The book also recycles the economic anti-Semitism of Karl Marx, who described Judaism and the Jewish culture as necessarily capitalist and capitalism as fundamentally Jewish.[liv] Simultaneously, Vladimir Bolshakov accuses the Zionists to have been “accomplices of the pogroms” in Ukraine, largely because of the presence of “Zionists” (in fact, Ukrainian patriots who happened to be Jewish) in the Petliura cabinet and because of the friendship between Petliura and Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky.[lv]

In fact, Petliura gave orders against the pogroms, obtained the trial, the death sentence and the execution of several perpetrators (unlike the Bolshevik leaders, who gave impunity to the pogromists of the Red Army), allocated an important sum for the victims who survived and the plan of the mixed gendarmerie prepared after 1921 with his friend Jabotinsky was not only aimed to fight against the Bolsheviks, as Vladimir Bolshakov alleges, but also, if not more, to prevent a renewal of pogroms in case of liberation of Ukraine.[lvi] Vladimir Bolshakov even dares to allege, without any archival document of course, that “the Zionists” were accomplices of the Nazi massacre of Babi-Yar.[lvii] In fact, a survivor blamed “the disciples of Stalin” as executioners, in the New Leader (5 January 1953).

Yet, Vladimir Bolshakov did not stop his activities in 1987 or in 1991. He became an enthusiastic supporter of Vladimir Putin and wrote a favourable biography of him. In 2013, he also published a book entitled: Marine Le Pen. Why Russia does need her? He did not stop writing against the Jews, quite the contrary. In 2014, he published another book, S talmudom I krasnym flagom (“With the Talmud and Red Flag”), where he described Lev (Leon) Trotsky as the leader of an anti-Russian “conspiracy,” merging the anti-Semitism of Stalin with the one of the Tsarist far right. The same year, Vladimir Bolshakov published another book, Blue Star Against Red Star: How the Zionists Became the Gravediggers of Communism, where he alleges that the Zionist, and especially Golda Meir (who died thirteen years before the collapse of the USSR) to be the main responsible.

More productive than ever, Vladimir Bolshakov devoted still another book to the assassination of the Romanov family in 1918 and called it a “Zionist ritual crime,” a clear allusion to the blood libel of the “Jewish ritual crimes.” Russian state TV correspondingly affirmed that the Jews were behind the Ukrainian revolution of 2014 and are “preparing a second Holocaust with their own hands, just as they did the first one” (sic), a regurgitation of the Soviet propaganda of 1952-1953 then of 1970s-1980s, assimilating Zionism and Nazism. Correspondingly, as early as 2013, Vladimir Bolshakov had published a book (yes, still another one) entitled Khazaria and Hitler.[lviii] Khazaria was a Middle Age kingdom whose royal family and aristocracy adopted Judaism. In 20th Century, emerged the myth that the Ashkenazi Jews are the descendants of Khazars. Not anti-Semitic as such, this theory was widely used by anti-Semites since 1970s.[lix] Khazaria and Hitler is just a continuation of the Stalinist efforts to assimilate the Jews to Nazism.

Yet, Vladimir Bolshakov is far from being the sole and only element of continuity with today.

The Soviet legacy and the war on Ukraine

Vladimir Putin is a former KGB official and his world view is largely based on his Soviet years. He entered the KGB school in 1984, namely at the paroxysmal moment of Soviet anti-Semitism and the year after the 50th anniversary of the Ukrainian famine of 1932-1933, a crime commemorated by the Ukrainians abroad, to the great displeasure of Moscow. He made his political ascension during the 1990s, yet the Duma, the Russian Parliament, claimed Sevastopol to Ukraine in 1992, 1993 and 1996. Anti-Semitism and neo-Nazism exploded in Russia during the 1990s and were almost never repressed. Even the perpetrators of the pogrom of Riazan (2000) received symbolic fines.[lx] As early as 1999, surveys indicated that Stalin, the mastermind of the famine of 1932-1933 and of the project to deport the Soviet Jews to Siberia, was positively perceived by 50% of the Russians,[lxi] in spite of all the revelations on his crimes since 1985.

During the 2000s, and even more after tightening of his dictatorship in 2011-2012, Mr. Putin has launched a work of rehabilitation of Stalin, making increasingly difficult and eventually impossible to make a serious work on Stalinism, as well as on the Russians who fought on the Nazi side, the Vlasov Army for example.[lxii] In 2025, he even ordered to install in the metro of Moscow a replica of the monument dedicated to Stalin until 1961. In 2019, a survey showed that 46% of the interviewed Russians considered justified the sacrifices in human lives during the Stalinist period, in the name of the material progress, while 45% answered that such losses cannot be justified. In June 2018, the Russian Public Opinion Research Center published a list of 20th century’s first half figures favored by Russians, with the top three positions occupied by Nicholas II (54%), Stalin (51%), and Lenin (49%).

This podium should not surprise anyone. Nicholas II, the most anti-Semitic Tsar, who protected the perpetrators of pogroms and fought the Ukrainian language, has been rehabilitated as early as 1990s. The favourite political writer of Mr. Putin is Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954). Ilyin was a reactionary monarchist during the reign of Nicholas II. During the interwar, he called himself a Fascist and publicly praised the first year of Hitler’s government, including as far as anti-Semitism was concerned. He broke up with the Nazis in 1938, because they persistently refused to include the Russians in the “Aryan race.” After 1945, he criticized the “errors” of the Nazi and Fascist regimes (but not their crimes, such as the Holocaust) and found in Franco and Salazar (who had self-described Fascists in their government) the best models for the future. One of the recurrent topics in Ilyin’s recommendation for a post-Soviet Russia was to fiercely oppose any Ukrainian effort to become independent. He referred to Ukraine as “Little Russia,” like the Russian reactionary never ceased to be.[lxiii] In 2008, Mr. Putin answered U.S. President George W. Bush by a quasi-copy of Ilyin’s words: “[Ukraine] is not a nation built in a natural manner. It’s an artificial country created back in Soviet times.” Such a claim is utter nonsense. The first independent Ukrainian Republic emerged in 1918-1919 against Bolshevik Russia. In a biography of Swedish king Charles XII, who had allied the Ukrainians against Muscovy, Voltaire wrote in 1731: “Ukraine has always aspired to be free.”

In 2015, a statue of a Russian far rightist even more extreme than Ilyin, Pyotr Krasnov, theorician of a Cossack Nazism, who led a unit of volunteers for the Third Reich, was unveiled in Russia. Alexei Milchakov, a Russian officer in occupied Ukraine since 2014, introduces himself as follows: “I am Nazi! I am Nazi.”

Regardless, the Russian diplomacy and propaganda remain largely Soviet-styled. The Kremlin provided crypto currency to the Palestinian Islamic Jihad before the massacres of 7 October 2023 and welcomed the Hamas after these killings of unarmed civilians, in full continuity with the Soviet support for the PLO. Russia provided weapons to the Hezbollah, as the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared in October 2024, on the basis of what was seized in the depots of that Islamist organization. Quite regrettably, Mr. Netanyahu never imposed any sanction on Russia, even after 2023-2024, not even anything similar to what has been imposed by Turkey, Kazakhstan or China. Quite the contrary, high tech machines making weapons have been sold to Russia. Mr. Netanyahu’s promise to deliver de-commissioned tanks to Ukraine never was fulfilled. This is not a considerable extrapolation to assume that Jabotinsky, the friend of Petliura, Menahem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, two of the most loyal allies of Washington during the Cold War, would be shocked.

Anyway, with a typically Soviet audacity, the Kremlin calls his ambitions against Ukraine “de-Nazification,” citing the (relatively rare) tributes to the OUN-B/UPA to substantiate its claims. Yet, while Bandera unfortunately had the idiotic prejudices of many European (and American) right-wing nationalists of the time, he was put in jail, and later in a concentration camp, by the Nazis for having proclaimed an independent Ukraine in June 1941. The OUN-B was beheaded by the occupiers the same year. The tactical collaboration with the Third Reich, aimed to alleviate the ordeal of the Ukrainian population, was found fruitless by the OUN-B in October 1942 and the UPA was established in February 1943, after months of preparation, to fight the Nazis and the Bolsheviks.[lxiv] Feodor Vovk, the second man of the OUN-B, was recognized, with his wife, as righteous among the nations in 1988. After 1991, the Ukrainian far right, even in the broadest sense of the word, never reached 5% of the votes, in absolute contrast with the American, French, German, Italian, Dutch, Scandinavian and Polish contemporary far rights, and in spite of much more painful economic difficulties. In 2019, the Ukrainians elected a Jew as President with 75% of the votes. Another Jew, Volodymyr Groysman, was the Ukrainian Prime Minister from 2016 to 2019.

Remarkably, Moscow never spoke about “de-Nazifying” Armenia when this country was ruled by the staunchly pro-Russian Republican Party (1998-2018), yet this party intensified the tributes to Nazi war criminals Garegin Nzhdeh and Drastamat “Dro” Kanayan. The Kremlin became aggressive against Armenia only after this country started distancing itself from both Russia and the ideology inherited from Nzhdeh and Dro, namely since 2022.

This “de-Nazification” slander against Ukraine is in continuity with the Soviet propaganda of 1952-1953 then of 1970s and 1980s, aimed to Nazify the Jews. An extreme example is provided by this contemporary Russian cartoon, reminiscent of those of 1970s:

Mr. Zelensky is attacked simultaneously as a Jew (as it is obvious with the David star, the kippa, the nose and ears copied from the most traditional anti-Semitic cartoons) and as a “Nazi.” In the text, he is supposed to say “We, Ukrainian Jews, are a holy people.” This copy of the Soviet propaganda is coherent with the recurrent Soviet symbols used by the Russian army in occupied Ukraine since 2022.

Yet, this propaganda is exported to the West. Here, only some of the some striking cases in three countries (U.S., UK and France) will be studied.

In the U.S., the most obvious example is Tucker Carlson, fired by Fox News in 2023 for being “uncontrollable” and since then a far rightist podcaster. In September 2024, Mr. Carlson interviewed Holocaust denier Darryl Cooper. They agreed that “Churchill was the chief villain of WW2” and Hitler “didn’t want to fight.” A year later, Mr. Carlson kindly interviewed white supremacist and Holocaust denier Nick Fuentes (and was not excluded from the Make America Great Again milieu in spite of the outcry it provoked). Mr. Carlson is also one of the main pro-Russian propagandists in the U.S. For example, in December 2023, he manipulated a statement of Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in order to scare his audience. Then, he interviewed Vladimir Putin himself. On 31 January 2025, he made not less than 74 false claims against Ukraine. These are not words only: Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell explained that Mr. Carlson was one of the two main responsible for the suspension for the American aid to Ukraine from November 2023 to April 2024.

Candace Owens, a caricature of anti-Semitic influencer, summarized her views on the Russian invasion as follows: “Fuck Ukraine!” Likud leader Dan Illouz rightfully called Mr. Carlson and Ms. Owens the “new enem[ies] rising from within” the main ally of Israel, but did not draw, so far, all the logical conclusions from it.

In UK, the continuity with the Soviet period is sometime even clearer. Andrew Murray was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain from 1976 to mid-2010s, and a firm supporter of Brejnev’s and Andropov’s USSR. In 1986 and 1987, he worked for Novosti Agency, the Soviet service described in the previous part of this article. He served as top advisor of Jeremy Corbyn from 2017 to 2020, namely when Mr. Corbyn protected vituperative anti-Semites in the British Labour Party. Mr. Murray himself continued to spread Soviet-styled “anti-Zionism”. Yet, he is also a supporter of Mr. Putin since at least 2008, when he approved the Russian invasion of South Ossetia (while it is a blatant violation of the UN Charter, of the Helsinki Final Act and of the Alma-Ata Declaration). He called the Ukrainian revolution of 2014 a Fascist coup and helped to organize demonstrations in front of the Ukrainian embassy. He also expressed doubts about the shooting of a Dutch civilian jet by the Russian forces, the same year. [lxv] Yet, Russia has been sentenced by the European Court of Human Rights for this shooting, for the invasion of 2014 and for the one of 2022. Mr. Murraw also gave an interview to Russia Today (a propaganda organ banned in the EU and UK since 2022) in January 2018 and another to former MP George Galloway the same year.[lxvi]

The record of Mr. Galloway and his party in anti-Semitism is so heavy that a long article would be barely enough to summarize the subject. He has persistently mirrored the Kremlin propaganda against Ukraine and its allies, claiming in November 2024 that “None of the attack ’ems or Storm Shadows hit their targets” (while the opposite is true), affirming without laughing, in November 2025, that “The Russians could be in Kiev by Christmas,” alleging that the West violated the Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015 (while they were violated by Russia) and opposing the Franco-British project of deployment of troops in Ukraine.

Another former MP, Chris Williamson, who established another small party, Resist, has a similar stance. In 2020, Resist planned a festival inviting Noam Chomsky (who praised Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson) dedicated to the Yellow Vest movement in France, yet this movement was largely infiltrated by Russian agents, including Xavier Moreau, who is now under European sanctions. In March 2022, Resist organized a meeting on “Zionism in Ukraine” (sic) mixing “anti-Zionism” with the Russian propaganda against Ukrainian patriotism.

In France, Alain Soral (pen name of Alain Bonnet), a fashionable writer turned into a far rightist firebrand around 2004, has been sentenced more than twenty times, since 2008, for defamation, hate speech, Holocaust denial and racist slurs. He has been a member of the National Front (now named National Rally) from 2005 to 2009 then continued to support the party from outside, inciting his supporters to be members of the Front in order to promote “anti-Zionism” in the party. He broke up with Marine Le Pen after her disastrous debate against Emmanuel Macron in 2017. He is a self-described admirer of Vladimir Putin, and loves to wear t-shirts with the Russian dictator’s picture. He called him on 14 June 2014 “someone who represents Aryan (even if Slavic) virility” (sic) and visited Moscow several times, including in May 2025, when he was welcomed by the authorities and delivered a speech inextricably mixing anti-Semitism with anti-Ukrainian hatred. His web site is one of the main relays, in France, of Russian propaganda against Ukraine and the West, announcing, for example, “the inevitable Russian victory in Ukraine,” nothing less. The OSINT specialists beg to disagree. We already saw Mr. Soral in my article “Paris-Moscow-Washington”.

Conclusion

The “Putinite syncretism” still gives a large part to Soviet propaganda methods and ideas. Current propaganda in the West target conservatives, while Stalin is a national hero in today’s Russia, advocates of national sovereignty while Russia invade neighbors, voters concerned by Islamism while Moscow is the biggest enabler of Islamism in the world, and anti-imperialist leftists while Russia is the most aggressively imperialist power today. Rational argumentation on historical legacies and contemporary practices is a must.

[i] Kevin D. Glathar, “From the Pale: The Russians and the Jews,” in Edward J. Erickson (ed.), A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare, London-New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2019,pp. 141-156; John Klier and Shlomo Lambroza (ed.), Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History, Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992; Tetuya Sahara, “Anti-Semitism in the Ottoman Empire and the Implication for Russia,” in Ömer Turan, The Ottoman-Russian War of 1877-78, Ankara-Tokyo: Middle East Technical University/Meiji Institute of Humanities, 2007, pp. 137-138; Giovanni Savino, “A Reactionary Utopia: Russian Black Hundreds from Autocracy to Fascism,” in Marlène Laruelle (ed.), Entangled Far Rights. A Russian-European Romance in Twentieth Century, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburg Press, 2018, pp. 36-44.

[ii] William Korey, “The Origins and Development of Soviet Anti-Semitism: An Analysis,” Slavic Review, Vol. 31, No. 1, March 1972, pp. 113-114; Alfred A. Skerpan, “Aspects of Soviet Antisemitism,” The Antioch Review, Autumn, 1952, Vol. 12, No. 3, p. 294; Solomon M. Schwarz, The Jews in the Soviet Union, Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1951, pp. 276-277.

[iii] Arkadi Vaksberg, Staline et les Juifs. L’antisémitisme russe : une continuité du tsarisme au communisme, Paris : Robert Laffont, 2003, pp. 76-77.

[iv] Ibid., p. 96.

[v] Ibid., p. 104.

[vi] Alfred A. Skerpan, “Aspects of Soviet…”, p. 306.

[vii] Arkadi Vaksberg, Staline et les…, p. 103.

[viii] “RUSSIA: Anti-Semitism?”, Time, 14 November 1938.

[ix] S. J. Taylor, Stalin’s Apologist. Walter Duranty: The New York Times man in Moscow, New York-Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990.

[x] Gedeon Haganov, Le Stalinisme et les Juifs, Paris : Spartacus, 1951, p. 3.

[xi] William Korey, “The Origins and…” p. 118.

[xii] Laurent Rucker, Staline, Israël et les Juifs, Paris : Presses universitaires de France, 2001, pp. 219-221, 247-271 and 274.

[xiii] Ibid., pp. 275-278 ; Léon Poliakov, De l’antisionisme à l’antisémitisme, Paris : Calmann-Lévy, 1969, pp. 70-73 ; Solomon M. Schward, “The New Anti-Semitism of the Soviet Union: Its Background and Its Meaning,” Commentary, June 1949.

[xiv] Jean-Paul Sartre, « Il n’y a plus de doctrine antisémite », Évidences, janvier 1952, p. 7.

[xv] Artur London, The Confession, London : MacDonald, 1970 (1st edition, in French, 1968); Mordecaï Oren, Prisonnier politique à Prague, Paris : René Julliard, coll. « Les Temps modernes », 1960 ; Laurent Rucker, Staline, Israël et…,pp. 278-286. Sartre controlled the collection « Les Temps modernes » (named after his review). He also wrote a particularly warm praise for London’s book. It is far from nullifying the rest of his comments on several Communist dictatorships, but it does not make these ones less remarkable, on the contrary.

[xvi] Léon Poliakov, pp. 91-92 ; Laurent Rucker, Staline et les…, p. 297.

[xvii] Arkadi Vaksberg, Staline et les…, p. 240.

[xviii] Ibid., pp. 241-257 ; Jonathan Bren and Vladimir Naumov, Stalin’s last crime: The plot against the Jewish doctors, 1948-1953, New York: HarperCollins, 2003.

[xix] Anthony Mostrom, “The Fascist and the Preacher: Gerald L. K. Smith and Francis Parker Yockey in Cold War–Era Los Angeles,” Los Angeles Review of Books, 13 May 2017; Anthony Mostrom, “America’s ‘Mein Kampf’: Francis Parker Yockey and ‘Imperium’”, Los Angeles Review of Books, 8 August 2020.

[xx] Walter Laqueur, “The Oren Case: A Fellow-Traveler Comes Home,” Commentary, August 1956.

[xxi] John Rogge, The German Official Report. Nazi Penetration, 1924-1942. Pan-Arabism, 1939-Today, New York-London: Thomas Yoseloff, 1961, pp. 366 and 369;Arkadi Vaksberg, Staline et les…, pp. 266-277.

[xxii] D. F. Green [Yehoshafat Harkabi and David Littman] (ed.), Arab Theologians on Jews and Israel, Geneva: Éditions de l’Avenir, 1976 (1st edition, 1971).

[xxiii] William Korey, “The Origins and…” pp. 123-124. On precursor signs of intellectual mediocrity in Stalin’s USSR in 1936, see André Gide, Return from the U.S.S.R., New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1937, p. 42 (translated from French by Dorothy Bussy).

[xxiv] Nicolas Lebourg, Le Monde vu de la plus extrême droite, Perpignan, Presses universitaires de Perpignan, 2010, pp. 137-138.

[xxv] Arkadi Vaksberg, Staline et les…,p. 278.

[xxvi] Carolyn Burch, “Russian orthodox scholar criticises Soviet anti‐semitism,” Religion in Communist Lands, Vol. 14, No. 1, 1986, pp. 97-99 ; Léon Poliakov, De Moscou à Beyrouth. Essai sur la désinformation, Paris : Calmann-Lévy, 1983.

[xxvii] An abbreviated version in French: Le Rôle du sionisme dans le génocide arménien, Athènes, ASALA, 1985. An English translation exists since 1992, but it has not been possible to read it before the publication of this article.

[xxviii] Léon Poliakov, De Moscou à…., p. 287.

[xxix] Izabella Tabarovsky, “Demonization Blueprints: Soviet Conspiracist Antizionism in Contemporary Left-Wing Discourse,” Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism, Vol. 5, No. 1, Spring 2022, pp. 3-5.

[xxx] J. Ilyina, The evolution of the Crimean Tatar national identity through deportation and repatriation, Master thesis, Leyde University, 2014, p. 28.

[xxxi] Alan W. Fisher, “Emigration of Muslims from the Russian Empire in the Years After the Crimean War,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Neue Folge, Bd. 35, H. 3, 1987, pp. 356-371; Mara Kozelsky, “Casualties of Conflict: Crimean Tatars during the Crimean War,” Slavic Review, Vol. 67, No. 4, Winter 2008, pp. 866-891.

[xxxii] Michael A. Reynolds, Shattering Empires. The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires, 1908–1918, Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 181-186 and 200; Jonathan D. Smele, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Ten Years that Shook the World, Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 54-57 and 96-98.

[xxxiii] General Anton Denikin, The Russian Turmoil, London: Hutchinson & C°, 1922, pp. 14, 190, and 248-249.

[xxxiv] Bohdan Nahaylo, “Ukrainian National Resistance in Soviet Ukraine During the 1920s,” Journal of Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 15, No. 20, Winter 1990, pp. 6-8.

[xxxv] William Edward David Allen and Paul Muratoff, Caucasian Battlefields. A History of the Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Borders, London-New York: Cambridge University Press, 1953, pp. 512-527.

[xxxvi] Paul du Quesnoy, “Warlordism à la russe: Baron von Ungern‐Sternberg’s anti‐Bolshevik crusade, 1917–21,” Revolutionary Russia, Vol.16, No.2, December 2003, pp. 19-21; Général Pyotr Wrangel, « La dernière campagne : Crimée 1920 », Revue des deux mondes, 1er mars 1930, pp. 106-134.

[xxxvii] Harold H. Fischer, The Famine in Soviet Russia. 1919-1923, New York-Toronto-London: MacMillan, 1927, pp. 246-266.

[xxxviii] La Famine en Ukraine, éditions du Comité de secours aux affamés de l’Ukraine, 1929.

[xxxix] Valentyna Boryssenko, « La famine en Ukraine (1932-1933) », Ethnologie française, XXXIV, 2004, p. 281-289.

[xl] Nicolas Werth, « Retour sur la grande famine ukrainienne de 1932-1933 », Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, n° 121, janvier-mars 2014, pp. 79-80.

[xli] See, for example, the letter of Mikhail Cholokoff to Stalin, 4 April 1933 and the reply of Stalin, 5 May 1933, translated in Nicolas Werth, “A State against Its People,” in Stéphane Courtois (ed.), The Black Book of Communism, Cambridge (MA)-London: Harvard University Press, 1999, pp. 166-167 (translated from French by Jonathan Murphy and Mark Kramer). Also see Oleg Khlevniuk, Stalin: New Biography of a Dictator, New Haven-London: Yale University Press, 2017.

[xlii] Stanley Morris, Stalin’s Famine and Roosevelt’s Recognition of Russia, Lanham: University Press of America, 1994, p. 87.

[xliii] Nicolas Werth, « Retour sur la… », pp. 81-82.

[xliv] Anne Applebaum, Red Famine. Famine War’s on Ukraine, London: Penguin Books, 2018.

[xlv] Victor Serge, Destiny of a Revolution, London: Jarrolds Publishers, 1937, p. 168 (translated from French by Max Schachtman). Initially Anarchist, Serge joined the Bolsheviks during the civil war, but became an internal opponent to Stalin by 1920s. Expelled from the USSR in 1936, he refused to join the Trotskyist international, considering, after reflexion, that the amoral stance of Leninism had made Stalinism possible: Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary. 1901-1941, London-New York: Oxford University Press, 1963 (translated by Peter Sedgwick).

[xlvi] Stephan M. Horak, « L’Ukraine entre les nazis et les soviétiques », Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale et des conflits contemporains, n° 130, avril 1983, pp. 66-67 ; Jay Weiser, “Ukraine’s Guerrilla War,” Persuasion, 4 March 2022.

[xlvii] Robert Belot, Vladimir Poutine ou la falsification de l’histoire comme arme de guerre, Lausanne : Fondation Jean-Monnet pour l’Europe, 2024, p. 53.

[xlviii] Peretz Pauline, « La grande famine ukrainienne de 1932-1933 : essai d’interprétation », Revue d’études comparatives Est-Ouest, vol. 30, n° 1, 1999, pp. 34-35.

[xlix] See the dates of publication in Oleh Pidhainy and Olexandra Pidhainy, Symon Petlura. A Bibliography, Toronto-New York: New Review Books, 1977.

[l] Alain Desroches, Le Problème ukrainien et Simon Petlura, Paris, NEL, 1962 ; FUP, The Black Deeds of the Kremlin. A White Book, Volume 2, Detroit: DOBRUS/Globe Press, 1955; O. Kalynyk, Communism. The Enemy of Mankind, London: The Ukrainian Youth Association, 1955; Murdered by Moscow: Petlura, Konovalets, Bandera, London: Ukrainian Publishers, 1962; Y. Onyshchuk, “A New Look at Simon Petlura,” New Review, No. 4-5, 1962, pp. 32-38; Olexa Woropay, The Ninth Circle, London: The Ukrainian Youth Association, 1954.

[li] Vladimir Brovkin, “Robert Conquest’s Harvest of Sorrow: A Challenge to the Revisionists,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, June 1987, Vol. 11, No. 1-2, June 1987, pp. 234-245 ; Guillaume Malaurie, « Le génocide par la faim », Le Monde, 29 août 1983.

[lii] Izabella Tabarovsky, “Demonization Blueprints: Soviet…”, pp. 8-9.

[liii] Vladimir Bolshakov, L’Anticommunisme, profession des sionistes, Moscow: Novosti, 1972, pp. 57-61.

[liv] Ibid., p. 5.

[lv] Ibid., pp. 5-18.

[lvi] Rémy Bijaoui, Le Crime de Samuel Schwartzbard, Paris, Imago, 2018, pp. 150-152 ; Taras Hunczak, “A Reappraisal of Symon Petliura and Ukrainian-Jewish Relations, 1917-1921,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 31, No. 3, July 1969, pp. 163-183; Israel Kleiner, From Nationalism to Universalism. Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky and the Ukrainian Question, University of Alberta Press, 2000.

[lvii] Vladimir Bolshakov, L’Anticommunisme, profession des…, p. 43.

[lviii] Walter Laqueur, Reflections of a Veteran Pessimist: Contemplating Modern Europe, Russia, and Jewish History, London-New York, Routledge, 2020, p. 128.

[lix] Typically Lucien Cavro-Demars, La Honte sioniste, Beyrouth, 1972, pp. 26, 29, 32, 51, 60, 86, 88-89 and passim. As the author himself explains, this book was published in Lebanon instead of France by fear of court cases for hate speech.

[lx] Arkadi Vaksberg, Staline et les…, pp. 293-298.

[lxi] Nicolas Werth, Poutine historien en chef, Paris, Gallimard, « Tracts », 2022, p. 52.

[lxii] Ibid., passim.

[lxiii] Anton Barbashin, “Ivan Ilyin: A Fashionable Fascist,” Iddle, 20 April 2018; Anton Barbashin and Hannah Torbun, “Putin’s Philosopher — Ivan Ilyin and the Ideology of Moscow’s Rule,” Foreign Affairs, 20 September 2015; Timothy Synder, “Ivan Ilyin, Putin’s Philosopher of Russian Fascism,” The New York Review of Books, 16 March 2018; Yuri Zarakhovich, “Putin Pays Homage to Ilyin,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 3 June 2009.

[lxiv] Stephan M. Horak, « L’Ukraine entre les… », pp. 69-74.

[lxv] Askold Krushelnycky, “Andrew Murray, banned from entering Ukraine, has long sympathized with Kremlin,” The Kyiv Post, 22 September 2018; Izabella Tabarovsky, “Demonization Blueprints: Soviet…”, p. 13.

[lxvi] Andrew Murray, “Jeremy Corbyn Aide, Barred From Ukraine Over ‘Links To Putin Propaganda Network,’” Huffington Post UK, 17 September 2018.

No responses yet