This episode analyses how Russian and Iranian propaganda networks systematically targeted the White Helmets to undermine evidence of war crimes in Syria. Leveraging psychological manipulation, narrative coordination, and conspiracy theories, this campaign illustrates a modern form of information warfare, implicating Western fringe figures and media platforms in amplifying state-sponsored falsehoods. It also links it to other uses of crisis actors by Russian linked influencers.

A recap from episode 1; reflexive control, a psychological tactic aimed at influencing an adversary’s decisions by shaping their perceptions; and Temnyk, centralised editorial directives, are critical tools employed in coordinated disinformation campaigns.

1. Introduction: A Rescue Group Turned Propaganda Target

White Helmets volunteers clear rubble after an airstrike in Ma’arat al-Nu’man, Syria (November 2014). This civil defence group became the target of an intense disinformation campaign by the Syrian regime’s allies, who accused them of being terrorists and of staging the very attacks they responded to. The White Helmets, officially known as the Syria Civil Defence, are volunteer first responders celebrated for saving countless lives in Syria’s war zones. Yet in parallel to their lifesaving work, a shadow narrative was constructed by state-sponsored media from Russia and Iran, painting the White Helmets as villains rather than heroes. In a coordinated propaganda offensive, these media outlets sought to undermine the group’s credibility by casting them as western-funded agents of chaos, even alleging they conspired to fabricate atrocities. This episode examines how those false narratives were orchestrated, highlighting the psychological and informational tactics – from repeated falsehoods to carefully timed “exposés” – used to attack the White Helmets’ reputation. It provides an evidence-based look at how Russian and Iranian state propaganda machine worked in concert to turn humanitarian witnesses into targets, illustrating broader strategies of state-sponsored disinformation.

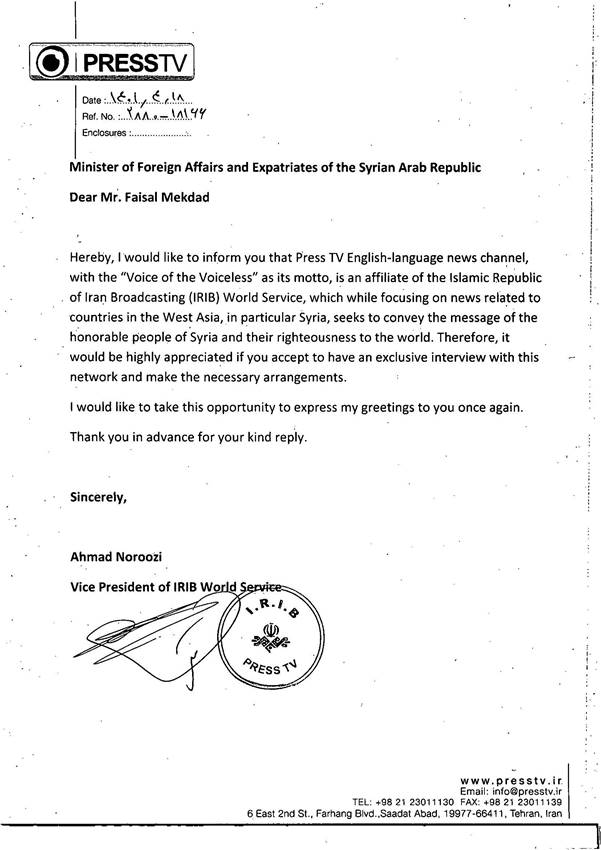

At the heart of this campaign is a troubling question: how did volunteer rescue workers end up “witnesses under fire” in an information war? Leaked scripts and internal documents from Iranian state broadcaster PressTV reveal a deliberate effort to coordinate narratives with Russia, weaving conspiracy theories that mirror Moscow’s claims. These sources offer a rare glimpse into the mechanics of propaganda – from editorial directives to talking points – showing how a false story can be built and amplified across borders. In the sections that follow, we will delve into these scripts and documents, uncovering direct quotes that expose the playbook used to smear the White Helmets. Through an accessible yet rigorous analysis, we will also introduce key concepts like “reflexive control” (a strategy of shaping an adversary’s decisions by manipulating their perceptions) and “Temnyk” (Moscow’s practice of issuing centralized media guidelines) to understand the sophisticated nature of this disinformation drive. By the end, it will become clear how the assault on the White Helmets exemplifies a broader propaganda strategy – one where Russia and Iran work hand-in-hand to challenge inconvenient truths and to control the narrative of the Syrian war.

2. Coordinated Narratives: Russia, Iran, and PressTV in Lockstep

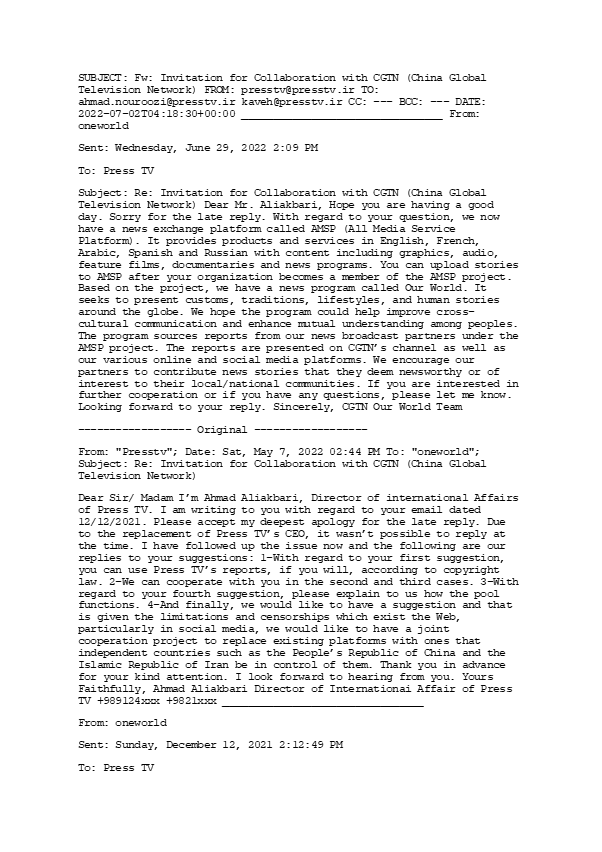

One striking feature of the campaign against the White Helmets is the synchrony between Russian and Iranian media narratives. PressTV – Iran’s English-language state broadcaster – frequently echoed and amplified stories originating from Moscow, suggesting a high degree of narrative coordination. This coordination is not coincidental; it is the product of a deliberate alliance in the information domain. In fact, internal Iranian documents reveal plans for formal media collaboration with Russia. One such document proposed creating an English-language news platform “in collaboration with RT/Sputnik in Russia to counter what Iran perceives as dominant Western narratives and amplify Iran-aligned perspectives,” aiming to provide an Iranian voice in global discourse. In other words, Tehran recognized that by teaming up with well-oiled Russian outlets, it could extend its propaganda reach.

The concept of Temnyk is useful to explain how these narratives stay so consistent. Originating from Russian media practice, a Temnyk is essentially an editorial directive or set of talking points issued to ensure all friendly outlets stick to the same story. Though Temnyks were first used domestically in Russia, PressTV’s content suggests a similar approach may be at play transnationally. Iranian and Russian outlets often pushed the exact same themes about the White Helmets – implying shared “instructions” behind the scenes. For example, both Russia’s RT and Iran’s PressTV consistently refer to the White Helmets with sceptical qualifiers like “so-called humanitarian group” or “controversial organization,” and both insinuate ties between the White Helmets and terrorist groups. This repetition of specific phrases and allegations across languages and platforms is a hallmark of coordinated messaging. It creates an echo chamber effect: a false claim made in Moscow is quickly repeated in Tehran’s media, giving audiences around the world the impression of a widely acknowledged truth. The result is a monolithic narrative that crowds out dissenting voices and legitimate evidence. By presenting a united front, Russian and Iranian media aimed to dominate the information space on Syria, leaving little room for the White Helmets’ own story or for independent verification of facts.

PressTV’s internal files underscore this lockstep coordination. In an archive of program scripts, each proposed episode had to be explicitly approved by Iranian authorities, indicating top-down control of content. The same files show that PressTV producers were keenly aware of Russian talking points and often built their shows around them. The White Helmets became a recurring focus, framed not as rescuers but as part of a Western plot. By examining these scripts, we see Iran’s state media essentially acting as a relay station for Russia’s messaging, adapting it for an English-speaking audience. The partnership goes both ways: Iran amplifies Russian narratives, and in return benefits from the credibility of Russia’s international media presence. Ultimately, this alliance treats information as another battleground – one where controlling the narrative is as important as any military gain on the ground.

3. White Helmets Under the Propaganda Microscope

From the moment the White Helmets gained international acclaim for their rescue efforts, they also attracted an extraordinary level of scrutiny and smear from state propagandists. Russian and Iranian outlets dissected the group’s every action, not to understand their heroism, but to find (or fabricate) any detail that could be twisted into a scandal. PressTV, for instance, ran multiple segments questioning the White Helmets’ legitimacy. A typical PressTV voice-over would describe them as “a controversial so-called civil defence organisation in Syria” that had been “hailed by the West as a fearless rescue organization” but was now supposedly “struggling to maintain its reputation” amid allegations of terror ties. Right away, the framing plants doubt: referring to the White Helmets as “so-called” civil defence primes the audience to suspect that the group is not what it seems.

What followed was a barrage of fabricated claims and innuendo. PressTV broadcasts, mirroring Russian narratives, asserted that “information [was] emerging of direct ties” between the White Helmets and extremist groups like al-Qaeda, as well as with Western intelligence. No credible evidence was provided for these grave accusations; instead, the claims were propped up by circular citing of regime-friendly “investigations” and hand-picked commentators. For example, PressTV often featured Vanessa Beeley, introduced as an “investigative journalist” who had “followed the White Helmets’ activities closely.” Beeley is known as a vocal critic of the White Helmets, and through PressTV she declared that the group had been “disgraced” and would be “sidelined” in favour of another entity. By giving Beeley a platform, state media imbued their narrative with a veneer of independent verification—when in reality, she was part of the same propaganda ecosystem, often appearing on both Iranian and Russian media with identical talking points.

The propaganda microscope focused on the White Helmets magnified every misstep or association, however tenuous, into evidence of malfeasance. If a White Helmets volunteer appeared in a photo with a firearm (perhaps because he picked it up in a conflict zone), it was broadcast as proof of militant ties. If equipment bore logos of Western donors (such as USAID, which openly funded the group’s rescue equipment), it was spun as proof of a CIA conspiracy. PressTV even suggested that the very name “White Helmets” was a branding ploy by Western PR firms, rather than an organic nickname (White Helmets: humanitarian group in Syria or terrorist affiliates?). By relentlessly questioning who the White Helmets really were, the propagandists aimed to sow uncertainty. The goal was to invert the narrative: instead of being seen as impartial saviours amid carnage, the White Helmets were to be seen as agents in a grand deception. Through repetition, selective “evidence,” and authoritative narration, this false image was pressed onto the public consciousness. In the coming sections, we will break down some of the most prominent fabricated claims and how they were coordinated across state media channels.

4. Fabricating a Terrorist Image: False Claims and Conspiracy Theories

To turn public sentiment against the White Helmets, Russian and Iranian propaganda constructed a portrait of the group that was not only unflattering, but outright terrifying. The White Helmets were accused of the worst crimes imaginable, with allegations escalating into bizarre conspiracy theories. A prime example comes from an NGO cited in a PressTV segment – tellingly named the “Fund for Research of Problems of Democracy” – which claimed the White Helmets “killed women and children with the aim of blaming government forces for the atrocities.” It further alleged that photos frequently showed White Helmets “directly engaged in hostilities” against civilians alongside terrorist groups. These are extremely grave charges – essentially painting the rescuers as murderers in disguise – yet they were presented to viewers as credible findings from a research organization. Not mentioned was the nature of this “Fund” itself, which is a Moscow-based outfit known for pushing pro-Kremlin narratives. By laundering the claim through an NGO, the propaganda gives a false impression of independent confirmation.

PressTV and its allies didn’t stop at murder accusations. They wove an elaborate theory that Western powers were orchestrating a fake humanitarian effort to destabilize Syria. In this narrative, the White Helmets were just one façade; when their reputation began to falter, the story went, the West propped up a new group called “the Violets” as a replacement. Vanessa Beeley promoted this idea, saying the White Helmets and the Violet organisation were “two different names with the same mission of destabilizing Syria” and operating in al-Qaeda–held areas. Such a claim suggests that even humanitarian aid groups are part of a vast militant network – a classic conspiracy theory pattern where nothing is as it appears. Beeley went further, asserting on-air that “Violet is part of the cartel that is profiteering from human trafficking, from organ trafficking”. By introducing horrifying elements like organ trafficking, the propagandists sought to evoke visceral disgust, effectively demonizing anyone associated with these groups.

These falsehoods were reinforced by selective use of quotes and endorsements from officials of Syria and its allies. Bashar al-Assad himself was featured in propaganda pieces, questioning the background of White Helmets’ founder James Le Mesurier and concluding that the White Helmets “are a natural part of Al-Qaeda”. Russia’s UN Ambassador Vassily Nebenzia similarly was quoted saying “The White Helmets deserve to be on the United Nations’ designated terrorist list”. By broadcasting such statements, state media gave the impression of an international consensus forming that the White Helmets were terrorists. It’s important to note that these claims had no basis in fact – multiple independent investigations (by the UN, journalists, and NGOs) have debunked them, and on the contrary, have documented the White Helmets’ humanitarian contributions (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda …). But in the realm of propaganda, perception is reality: repeating a lie often enough, and from the mouths of high-level figures, can make it stick. Each new fabricated claim – no matter how outlandish – was another thread in a narrative tapestry meant to rebrand the White Helmets from life-savers to life-takers.

5. The Douma Drama: A Case Study in Narrative Warfare

The events surrounding the April 2018 chemical attack in Douma provided a pivotal moment for the propaganda war against the White Helmets. In Douma, a suburb of Damascus, the White Helmets filmed the chaotic aftermath of what appeared to be a chemical strike on civilians. Those harrowing images – of children gasping for air and being hosed down in a clinic – went viral worldwide and led Western governments to blame and strike the Syrian regime. Almost immediately, Russia and Iran moved to counter this narrative with an alternate version of events, one that would exonerate their ally in Damascus and implicate the White Helmets as fraudsters.

PressTV broadcasts on Douma closely followed the Russian line. They reminded viewers that the incident came “just as Syrian government forces were about to liberate the city from terrorist groups”, insinuating that the timing was suspicious. The implication was clear: why would Assad gas civilians in a city he was on the verge of winning back? The propagandists answered their own question by asserting it was a “false flag” – staged by the White Helmets under Western orders. One PressTV voice-over, parroting Moscow’s claims, stated flatly: “Moscow says it has evidence that in early April 2018, the White Helmets were put under serious pressure by the UK to speed up the staged attack.” London denied this, but the report continued, “It was this fake operation that served as the pretext for US, French and UK missile strikes on Syria.” In this telling, the suffering in Douma was not a regime crime but a theatrical production directed by foreign intelligence – a complete inversion of culpability.

To bolster this narrative, Russia undertook an extraordinary propaganda stunt: it flew supposed eyewitnesses of the Douma event to the headquarters of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague. There, a young Syrian boy and medics from the video were presented in front of international media to testify that no chemical attack had occurred, and that the White Helmets had made them participate in a staged video. PressTV and RT covered this spectacle extensively. They highlighted statements by Russia’s OPCW representative Alexander Shulgin, who claimed Russian experts “were able to find the Syrians who had been shown in the White Helmets video as the victims of the poisonous substances” and bring them to testify. Shulgin even cast doubt on other incidents, alleging that footage from a previous attack in Khan Shaykhun had mysteriously vanished because it was fake. These quotes, laden with technical detail and confident assertions, were used to construct an air of forensic debunking – as if Russia had proven the hoax. (In reality, independent chemical weapons investigators later reaffirmed that a chemical attack in Douma did occur, and criticized the Russian show at The Hague as a brazen misinformation exercise.)

The Douma case study shows narrative warfare in its full dimension. On one side, evidence on the ground (videos, gas canisters, victim symptoms) and journalistic investigations pointed to a chemical atrocity by Syrian forces. On the other side, a swift counter-narrative – armed with alternative witnesses, diplomatic press events, and saturation media coverage – painted it as a fake news story concocted by the White Helmets. For observers, the truth became entangled in claims and counterclaims. This confusion was exactly the point. By throwing up dust and fostering doubt, the Russian-Iranian propaganda machine aimed to neutralize the impact of the Douma revelations. If enough people believed the White Helmets faked it, or even just weren’t sure what to believe, then the outrage against Assad could be defused. In essence, Douma’s information battle demonstrated how propagandists can weaponize scepticism – using real witnesses as pawns and broadcasting meticulous-sounding details – to rewrite the narrative of a war crime in real time.

6. Reflexive Control: Manipulating Perceptions as Strategy

Underlying these propaganda campaigns is a strategic concept known as reflexive control. Originating in Soviet military thought, reflexive control is essentially the art of getting your adversary to “make the decisions that one wants him/her to” by feeding them selective information (Disinformation and Reflexive Control: The New Cold War). It’s a psychological form of warfare, where instead of directly forcing an opponent’s hand, you cleverly shape the perceptions that drive their choices. In the context of the White Helmets, Russia and Iran practiced reflexive control on multiple levels. They aimed not only to influence the general public’s beliefs about the group, but also to affect the decisions of governments, international organizations, and even the White Helmets’ members themselves.

How does this work in practice? Consider the Western governments contemplating action against the Syrian regime for alleged chemical attacks. By loudly and repeatedly asserting that those attacks were “staged” by the White Helmets, Moscow’s hope was to introduce just enough doubt to make Western leaders hesitate or second-guess their intelligence. If the public in the US or UK started believing that maybe the White Helmets pulled a hoax – or even simply heard there was a controversy – politicians might face pressure to “wait for more evidence” or avoid intervention. In essence, the propaganda doesn’t need to convince everyone; it just needs to create uncertainty and division. This is reflexive control: shaping the information environment so the other side, reacting to a mix of truths, half-truths, and lies, ends up doing what you desire (in this case, refraining from action, or squabbling internally). Indeed, Russian officials openly gloated when segments of the Western public and alternative media picked up their Douma narrative, as it achieved the goal of muddying the waters.

Another aspect of reflexive control is pre-emptive narrative strike. Moscow and Tehran often anticipate what their opponents will do, and then put out a storyline that flips the script beforehand. For instance, knowing that the White Helmets document and publicize civilian casualties of Russian and Syrian bombings, Russian media pre-emptively labelled those videos as staged. The next time the White Helmets released shocking footage of an airstrike’s aftermath, a segment of the audience was already conditioned to cry “fake!”. By pre-emptively seeding conspiracy theories (like “White Helmets stage rescue scenes with crisis actors”), the propagandists influence how new information is interpreted reflexively – people reflect the planted narrative in their reaction. This technique has been honed in various conflicts. In Ukraine, for example, Russian info-warriors often accused Ukrainians of doing exactly what Russia planned to do, thus confusing observers about culpability. In Syria, the White Helmets became a prime target of such mirroring tactics. The net effect is a perception trap: whatever the White Helmets did or showed, propagandists would claim the opposite, leaving casual observers unsure of reality. This cynicism and confusion in audiences is not accidental; it is the intended outcome of reflexive control, because a confused or sceptical public is less likely to support measures that might hurt Russia or its allies.

By employing reflexive control, Russia and Iran turned information itself into a battlefield weapon. They leveraged psychological levers – mistrust of Western governments (playing on Iraq WMD fiascos, for example), fear of terrorism, even moral outrage at alleged atrocities – but redirected those emotions toward their own ends. In doing so, they illustrate how modern state propaganda isn’t just about broadcasting a message; it’s about anticipating and influencing how others respond to events. The White Helmets, unfortunately, were caught in this strategic crossfire – their real acts of heroism undermined by a web of calculated lies designed to manipulate perceptions far beyond Syria’s borders.

7. Temnyk Tactics: Orchestrating Unified Messaging

To achieve such tight coordination in messaging, the architects of disinformation rely on something very akin to the Russian Temnyk system. As mentioned, a Temnyk is an informal directive – essentially a memo of talking points – that is circulated to aligned media to ensure everyone sings from the same hymn sheet. While the specific term Temnyk comes from early 2000s Russian media practice, the underlying tactic has been adopted and adapted by other actors in the “information war,” including Iran. The leaked PressTV documents provide a fascinating look at how a Temnyk-style approach was used to synchronize narratives about Syria and the White Helmets between Tehran and Moscow.

One Iranian document obtained by the WOC lays out a strategy for joint media operations. It underscores the necessity of the project by noting how Western governments “expand their media influence yearly, suppressing alternative voices,” and how Iran needs to do the same to challenge Western narratives. The document acknowledges that countries like Russia had successfully created influential outlets like RT, whereas Iran was still struggling to have an impact internationally. The proposed solution was an English-language platform developed in partnership with Russian state media, effectively piggybacking on Russia’s experience and reach. The document explicitly suggests “partnering with RT and social media networks to amplify content” that challenges Western policies. In essence, this is Iran devising its own Temnyk pipeline: agreeing on content and frames with Russian counterparts, then pushing them out through multiple channels for maximum amplification.

The unified messaging we observed about the White Helmets – the identical accusations and even phrasing across RT, Sputnik, PressTV, and a host of pro-Kremlin blogs – is very likely the fruit of such coordinated planning. Temnyks typically include instructions on which narratives to push and which to downplay. In the case of the White Helmets, the directive was clear: highlight any alleged link to terrorism, question their funding and motives, emphasize any Western government connection, and assert they fabricate evidence. Conversely, downplay any stories of their genuine rescues or recognition (for example, when the White Helmets won international awards or were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, state media either ignored it or sarcastically dismissed it). The consistency of these angles across different outlets suggests a guiding hand. It’s quite possible that within the troves of leaked files there were literal briefing notes or emails saying, in effect, “Theme of the week: White Helmets as Western propaganda tools; use terms like ‘so-called humanitarian’ and cite X, Y, Z sources to question them.”

Another clue to Temnyk-style orchestration is the recurrence of the same personalities and sources in different propaganda pieces. We see the same “experts” (Beeley, et al.) and the same fringe organizations (e.g., that dubious “Fund for Research of Democracy”) popping up in reports from both Russian and Iranian outlets. This isn’t mere coincidence; it indicates an agreed-upon pool of sources that fit the narrative. When media in two countries quote the same obscure NGO report in the same week, you can suspect some behind-the-scenes coordination. Indeed, one leaked email even hinted at formal co-operation between Russian and Iranian media officials, showing direct communication lines about content sharing. Temnyk tactics turn media into an orchestra, with propagandists as the conductors cueing each section when to come in. The resulting symphony – in this case, the chorus of anti-White Helmets stories – feels persuasive to the audience because it’s everywhere, seemingly coming from multiple independent sources, when in truth it’s one composed piece. Recognizing the Temnyk element helps us see through the illusion of spontaneity in this propaganda: the harmony is deliberate, scripted, and directed.

8. Crisis Actor Conspiracies: From Sandy Hook to Syria’s War and beyond

Tsargrad TV and the Syrian Civil War’s ‘Crisis Actors’

Tsargrad TV was established in 2015 as a Russian ultra-conservative network, bankrolled by sanctioned oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev and engineered by ex-Fox News producer Jack Hanick (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times). Branded “God’s TV, Russian style” for its Orthodox nationalist bent, Tsargrad was explicitly modeled on Fox News as a mouthpiece for “traditional values” and pro-Putin ideology (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times). Under Malofeyev’s direction, the channel became a propaganda weapon aligning with Kremlin narratives – Malofeyev even decreed that while Tsargrad could criticize those in power, “one should not criticise Vladimir Putin… that is absolutely forbidden” (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times). In practice, Tsargrad relentlessly echoed the Kremlin’s line on foreign conflicts – notably the Syrian civil war – by painting Russia and its allies as besieged truth-tellers and their opponents as frauds.

During the Syrian war, the “crisis actor” trope became central to Tsargrad’s coverage and Russian state propaganda writ large. As Syria’s Assad regime, backed by Russia, faced global outrage over bloody sieges and chemical attacks, pro-Kremlin media sought to discredit reports of atrocities. They amplified baseless claims that these horrors were staged hoaxes. Volunteer rescuers – the White Helmets – were smeared as “crisis actors” fabricating carnage to blame Assad (How Syria’s disinformation wars destroyed the co-founder of the White Helmets | Syria | The Guardian). For example, after a 2017 sarin gas attack killed dozens in Khan Sheikhoun, Moscow’s officials and media outlets cynically alleged that the footage of dying civilians was faked by the White Helmets “using actors, as part of a Western conspiracy” (The Assad-Kremlin Attacks on the White Helmets – EA WorldView). Even Russia’s UK embassy tweeted that the White Helmets “are actors serving an agenda, not rescuers” (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian). This narrative of staged Syrian atrocities was echoed on Tsargrad and its sister platforms, casting Syria’s victims as merely paid performers. By flooding the information space with such falsehoods, Tsargrad and Kremlin outlets aimed to sow doubt over authentic evidence of war crimes (How Syria’s disinformation wars destroyed the co-founder of the White Helmets | Syria | The Guardian). The end goal was to undermine reality – to convince audiences that any heartbreaking image from Syria could be a theatrical fabrication by the West, rather than a result of Russian or Assad regime violence.

Alex Jones and the Sandy Hook ‘Crisis Actor’ Myth

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, American far-right broadcaster Alex Jones was popularizing the same pernicious narrative in a domestic context. Jones – whom Tsargrad even invited on-air as a kindred conspiracist (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times) – infamously claimed that the 2012 Sandy Hook elementary school massacre was a giant hoax. On his InfoWars platform, Jones insisted the mass shooting was “staged”, “synthetic”, “manufactured” – “a giant hoax” that was “completely fake with actors” (Alex Jones – Wikipedia). He promoted the vile idea that the grieving parents and slain children were merely crisis actors in a government plot to confiscate guns. This baseless lie spread to millions of his followers, illustrating how the “crisis actor” mantra could be weaponized to deny reality and stoke paranoia. Jones continued doubling down for years, also deriding other American tragedy survivors (like Parkland school shooting teen David Hogg) as “paid crisis actors” (Alex Jones – Wikipedia). The real-life consequences were severe: Sandy Hook families endured harassment and death threats from believers of Jones’s fiction (Alex Jones – Wikipedia). Juries would eventually award those families nearly $1.5 billion in defamation damages, underscoring the enormity of Jones’s deception. Yet for Jones and his audience, the “crisis actor” narrative became a keystone of their worldview – a shorthand to dismiss any mass casualty event as a staged provocation by shadowy “globalists.” The propaganda playbook was identical to Tsargrad’s: portray victims as villains in disguise, and facts as falsifications. Jones’s Sandy Hook hoax claims and Russia’s Syria hoax claims were two sides of the same conspiratorial coin.

Eva Bartlett and Vanessa Beeley: Echoing Kremlin Narratives in Syria

Crucial to bridging these narratives were a cadre of Western fringe commentators who parroted Russian propaganda. Eva Bartlett and Vanessa Beeley – often presented as “independent journalists” – became prolific amplifiers of the Syrian “crisis actor” fabrication. Bartlett, a Canadian activist, appeared at a Syrian regime-organized UN panel in 2016, where she alleged that the White Helmets stage rescue operations and recycle the same victims for dramatic effect (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian) (Network of Syria conspiracy theorists identified – study | Syria | The Guardian). (One viral video of her UN speech garnered over 4.5 million views (Network of Syria conspiracy theorists identified – study | Syria | The Guardian).) Similarly, British blogger Vanessa Beeley has tirelessly smeared the White Helmets as frauds – at one point claiming the “majority consensus” was that the group is a “fraudulent terrorist organisation” (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian). Both women have pushed the notion that scenes of Syrian civilians pulled from rubble or poisoned by gas were essentially theatre. Bartlett asserted that rescue videos were manufactured with “recycled” child actors (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian), a claim comprehensively debunked by independent reporters. These conspiracy narratives from Bartlett and Beeley neatly bolstered Assad’s and Moscow’s denialism.

Russian state media eagerly elevated Bartlett and Beeley as truth-tellers. They became regular fixtures on outlets like RT and Sputnik, receiving “flattering coverage by Russian and Syrian media” for their claims (How Syria’s disinformation wars destroyed the co-founder of the White Helmets | Syria | The Guardian). Indeed, experts noted that the Kremlin’s propaganda machine created a “manufactured consensus” by having the same handful of people – Bartlett, Beeley, and a few like-minded bloggers – cited across dozens of aligned websites and TV segments (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian). Their pseudo-expert commentary was repackaged endlessly, giving a false impression of widespread agreement that Syrian atrocities were staged. “They have a range of websites that will publish whatever nonsense – and Russia Today will have them on TV,” observed one analyst of this network (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian). In essence, figures like Beeley and Bartlett functioned as Western faces for an Eastern disinformation campaign. Their messaging closely intertwined with American conspiracy outlets as well: Beeley has written for InfoWars-connected blogs, and her claims were often echoed in far-right U.S. online circles. This chorus of Syria-hoax pundits provided a bridge, carrying the “crisis actor” narrative from Russian state media into the ecosystems of English-speaking conspiracy theorists.

A Coordinated Propaganda Ecosystem

The through-line between Tsargrad’s Syrian “crisis actors” and Alex Jones’s Sandy Hook hoax is a striking example of convergent propaganda. Both the Russian state media sphere and the American conspiracy milieu found common cause in these narratives, mutually reinforcing each other’s claims. Tsargrad TV itself literally hosted Alex Jones in a discussion led by Russian ultra-nationalist Aleksandr Dugin (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times), symbolizing the nexus of Kremlin ideologues and U.S. far-right conspiracists. Malofeyev’s operation and Jones’s InfoWars shared an ideological affinity – both railing against “globalist” plots, both eager to legitimize each other’s fringe ideas. Tsargrad, for instance, peddled anti-Western conspiracy theories about George Soros and satanic child-killers that would not be out of place on Jones’s broadcasts (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times). This alignment of worldviews made cross-pollination natural: Moscow could cite American truthers to validate its disinformation, while American conspiracists lifted Kremlin talking points to buttress their deep-state narratives.

The result was an echo chamber spanning Moscow to Texas, in which fabricated stories of crisis actors and false flags bounced back and forth. During the Syrian war, Kremlin officials and propagandists put forth the initial lie that atrocities were staged; Western fringe activists like Bartlett and Beeley then amplified those lies in English, lending them reach and pseudo-credibility (How Syria’s disinformation wars destroyed the co-founder of the White Helmets | Syria | The Guardian) (How Syria’s White Helmets became victims of an online propaganda machine | Syria | The Guardian). Their assertions were in turn fed into American conspiracy outlets (some with direct ties to InfoWars), ensuring U.S. audiences heard the “Assad is innocent, victims are actors” refrain. Conversely, the wild claims of Alex Jones – such as the idea that the U.S. government stages mass shootings with “crisis actors” – found receptive ears in Russian media that delight in portraying America as deceitful and malign. In this way, each side’s propaganda benefitted the other: Jones gave Kremlin outlets a Western poster-boy for anti-establishment “truth-telling,” while Kremlin disinformation gave Jones and his ilk international validation for their belief that all tragedies are orchestrated conspiracies.

Analysts have observed that Syria was a proving ground for this playbook, which has since been adapted elsewhere (Network of Syria conspiracy theorists identified – study | Syria | The Guardian). The crisis actor narrative, once a fringe eccentricity, evolved into a transnational propaganda tool. From Aleppo to Newtown, the same formula was deployed to erase victims and absolve perpetrators: call it a hoax, cast the victims as actors, and invert the truth. This overlapping info-war propaganda ecosystem – uniting Russian state media and American conspiracy influencers – has had real consequences. It muddied the waters during international crises, undermined public empathy for victims, and helped forge a global far-right fraternity united in paranoia. Ultimately, the “crisis actor” conspiracy theory served as a common language for Kremlin-backed media and alt-right provocateurs, allowing them to collaborate in manufacturing unreality on a global scale (How Syria’s disinformation wars destroyed the co-founder of the White Helmets | Syria | The Guardian) (The TV Exec, the Oligarch and the Global Far-Right – Byline Times).

9. Beijing Joins the Chorus: CGTN Amplifies the Smear

China’s state media has also lent its weight to the anti-White Helmets campaign, often in tandem with Iran’s. China Global Television Network (CGTN) has aired segments mirroring the Russian and Syrian narrative – even featuring the same fringe “experts” used by PressTV. For instance, in April 2018 CGTN ran a report from Douma suggesting the White Helmets had “produced fake videos” to blame the Assad government for a chemical attack (news.cgtn.com). The segment amplified claims by Moscow and Damascus that the incident was staged: “Russia blames…British intelligence [for] staging the attack…Damascus says [the] ‘White Helmets’ fabricated evidence” (news.cgtn.com)~. CGTN even gave airtime to British blogger Vanessa Beeley – a frequent PressTV guest – who alleged the White Helmets “work with terror groups” like Jaish al-Islam and serve as “a civil defence for the armed groups”(news.cgtn.com). This is the exact narrative that PressTV has promoted. In its own broadcasts and articles, PressTV routinely labels the White Helmets as so-called rescuers conspiring with jihadists. One 2021 PressTV report – citing the Russian Defence Ministry – claimed the White Helmets “carry out staged chemical attacks…in order to falsely incriminate Syrian government forces” and are essentially allied with terror outfits (presstv.ir). In short, Chinese and Iranian state outlets have been singing from the same hymn sheet, both broadcasting that the White Helmets are frauds or worse.

Beyond simply echoing each other’s content, there are indications of active cooperation between Beijing and Tehran in spreading these narratives. One joint initiative is CGTN’s new All Media Service Platform (AMSP) – a content-sharing program through which CGTN distributes packaged video news reports to partner outlets around the world for free (pressgazette.co.uk). By late 2023, AMSP hosted some 49,000 CGTN video segments and claimed “600 partner newsrooms” worldwide (pressgazette.co.uk). Many clips are innocuous news packages, but others push strategic narratives – for example, “fact-check” videos dismissing Western reports (like evidence of abuses in Xinjiang) in favour of Beijing’s line (pressgazette.co.uk). Iran’s PressTV stands to benefit from this arrangement: barred from Western media pools, PressTV can pull CGTN footage and scripts via AMSP to bolster its own newscasts. Indeed, PressTV already sources Chinese official statements and coverage for topics like Syria. In one story, PressTV highlighted remarks by “China’s UN envoy” urging a cooperative approach on Syria’s chemical-weapons file (presstv.ir) – a narrative that conveniently undercut Western pressure on Damascus. Through platforms like AMSP, Chinese state media content – including its spin on conflicts – is laundered into the programming of Iran’s state media and beyond. This kind of content swapping allows propaganda produced in Beijing to air in Tehran (and vice versa), cloaked with the credibility of a “foreign” source. It’s a mutually beneficial exchange: Chinese outlets amplify Iran’s talking points, and Iranian outlets get polished, ready-made packages that align with their worldview.

Both CGTN and PressTV have also participated in co-production forums and informal media alliances that aim to present a united front against Western narratives. Media cooperation conferences in recent years have emphasized “many voices, one world”–style messaging, bringing together broadcasters from China, Iran, Russia and other like-minded states. In 2017, China’s government-affiliated media explicitly called for deeper collaboration among international news outlets to “safeguard their common interests” and counter the Western monopoly on information (eprints.lse.ac.uk). This rhetoric translated into formal agreements: for example, in September 2018 China Media Group (CGTN’s parent company) signed a content-sharing deal with Russia’s Rossiya Segodnya (RT/Sputnik) to coordinate English-language news output (iswresearch.org). Iran, for its part, was developing a similar plan – a leaked proposal shows Tehran wanted to create a joint English-language platform “in collaboration with RT/Sputnik in Russia” to amplify Iran-friendly narratives globally. In essence, these state media players envision an alternative information order – sometimes nicknamed a “One World” media network – wherein Beijing, Moscow, Tehran and their allies pool resources to push a unified message. PressTV’s cooperation with CGTN thus fits into a broader pattern: just as Tehran aligned with Kremlin outlets, it also embraced China’s state media as an ally in the info-war. Each side boosts the other’s propaganda under the banner of “media cooperation,” blurring the lines between their narratives. For example, Chinese outlets have even given column space to Russian-aligned propagandists – CGTN regularly publishes commentary by Andrew Korybko, a Moscow-based American conspiracy theorist notorious for his Kremlin-approved takes(news.cgtn.com). By showcasing each other’s pundits and content, CGTN, RT, PressTV, and others create an echo chamber that spans continents.

This tight coordination between Chinese and Iranian media supercharges the process of narrative laundering. A dubious allegation can be planted by one outlet and then rebroadcast by others as if it were independent confirmation. We saw how a Kremlin-linked “NGO” report accusing the White Helmets of killing children was featured on PressTV as factual – without revealing the source’s Russian ties. The same principle extends to China’s CGTN: its Douma reportage cited a British blogger (Beeley) and Syrian officials to cast doubt on the White Helmets, giving viewers the impression that multiple voices – Western, Syrian, and Chinese – all questioned the group (news.cgtn.com). In reality, those voices were all part of the same Moscow-scripted chorus. By bouncing accusations across friendly outlets, state propagandists make falsehoods omnipresent. A lie told in Moscow gets repeated in Tehran, broadcast from Beijing, then maybe blogged about in Delhi or Caracas – each repetition adding a veneer of legitimacy. This multi-platform amplification is designed to muddy the waters for audiences worldwide. As one analysis noted, when Syria’s allies all started parroting that the White Helmets were terrorists, it created the “impression of an international consensus” against them. Such unanimity was of course an illusion – “these claims had no basis in fact” – but the perception of broad agreement can be powerful. By the time independent investigators debunked the falsehoods, the damage was done: enough doubt had been seeded to make uninformed observers wonder if the rescuers were villains. This is exactly how reflexive control works as an information strategy. By manipulating perceptions through coordinated lies, the architects of this disinformation hoped to influence their adversaries’ decisions – for example, deterring Western intervention in Syria by eroding the White Helmets’ credibility. In the court of public opinion, repetition confers authority. China’s CGTN and Iran’s PressTV, by recycling each other’s conspiracy claims, attempted to hammer the White Helmets’ reputation into rubble just as effectively as any airstrike could.

In summary, the collaboration between CGTN and PressTV to vilify the White Helmets shows the reach of today’s narrative war. Iranian and Chinese state media may come from different continents, but they are operating in concert to launder propaganda through a global echo chamber. Their joint initiatives – from content exchanges like AMSP to synchronized “exposés” – illustrate how disinformation can be transnational, leaping from one state-run outlet to another. By aligning their content with Russian and Syrian talking points, CGTN and PressTV have effectively formed a propaganda feedback loop: each validates and amplifies the other. This blending of narratives serves their shared geopolitical goal of undercutting Western accounts of the Syrian war. And by flooding the information space with recycled falsehoods under different logos, they make it harder for ordinary observers to trace the falsehoods back to their source. The case of the White Helmets is a textbook example of narrative laundering through alliance media. It demonstrates how reflexive control can be attempted on a global scale – with Beijing and Tehran together trying to shape reality as seen by audiences worldwide. Ultimately, the partnership between CGTN and PressTV in attacking the White Helmets underscores a sobering fact: in the disinformation age, authoritarian media find strength in numbers. By speaking in unison, they aim to drown out the truth with a chorus of convenient lies.

10. Alt-Media Amplifiers: VIPS and Antiwar.com’s Narrative Laundering

While Russian and Iranian state media orchestrated the White Helmets smear from abroad, a network of Western voices helped launder these narratives into mainstream discourse. Two prominent examples are Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS) – a group of retired U.S. intelligence officers – and the nonprofit Randolph Bourne Institute’s project Antiwar.com, a libertarian-leaning news site. Both lent an independent veneer to claims that Syrian chemical attacks were hoaxes or false flags, echoing Moscow’s line. VIPS, in a series of open letters, repeatedly challenged official findings on chemical attacks. Just days after the August 2013 Ghouta sarin massacre, VIPS wrote to President Obama claiming “the most reliable intelligence shows that Bashar al-Assad was NOT responsible for the chemical incident” (Syria’s Chemical Weapons: Assad Not to Blame, Say Truthers | The New Republic) – instead suggesting it was a rebel-led provocation. Five years later, on April 11, 2018, VIPS warned President Trump against striking Syria over the Douma attack, arguing one “must consider the possibility that the supposed chlorine gas attack at Douma may have been a carefully constructed propaganda fraud” aimed at trapping the U.S. in a war (Trump Urged to Seek Evidence Before Attacking Syria – Consortium News). In essence, VIPS promoted the White Helmets false-flag theory from within the West’s own expert community.

Notably, VIPS’s controversial memos drew on extremely dubious sources. Investigations found that their 2013 letter cribbed from fringe conspiracy sites (one paragraph was lifted almost verbatim from Global Research) and even cited an Infowars story (Syria’s Chemical Weapons: Assad Not to Blame, Say Truthers | The New Republic). In other words, VIPS laundered internet misinformation into an official-sounding “former intel officials’” report. Yet this gambit succeeded in muddying the waters. The VIPS letter circulated widely among anti-war activists and was even amplified by unlikely allies across the spectrum (Syria’s Chemical Weapons: Assad Not to Blame, Say Truthers | The New Republic). Russian officials also seized the opportunity: Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov publicly echoed VIPS’s arguments, referencing the ex-spies’ open letter in a UN speech to cast doubt on Assad’s culpability (Calling (Again) for Proof: 2013 Sarin Attack at Ghouta | HuffPost The World Post). By piggybacking on VIPS, the Kremlin narrative gained a patina of legitimacy – presented not as propaganda from Moscow, but as a sober warning from American intelligence veterans. This is narrative laundering in action: disinformation spawned on the political fringes was repackaged by VIPS and then touted by Russia as “independent” validation of its claims.

Parallel to VIPS, Antiwar.com played a key editorial role in amplifying Syria disinformation to Western audiences. The site – ostensibly anti-interventionist – became a hub for articles questioning every allegation of Assad’s war crimes. Its late co-founder Justin Raimondo epitomized this stance. In an April 2017 column (after the Khan Shaykhun sarin attack), Raimondo flatly asserted that the intelligence blaming Assad was “in fact, a lie, a hoax, a false flag operation undertaken by the Islamist rebels and their Turkish allies” (Trump Walks Into Syria Trap Via Fake ‘Intelligence’ – Antiwar.com). Such language, accusing Syrian rebels of gassing their own people to blame Assad, directly mirrored Russian and Syrian talking points. Antiwar.com continued in this vein through the Douma incident and beyond. It gave favourable coverage to leaked documents and whistleblower claims that purported to expose an OPCW cover-up. One Antiwar piece in 2020, for instance, suggested that “internal documents published by WikiLeaks indicate that many [OPCW] investigators… leaned towards the conclusion that the rebels fabricated the [Douma] incident but were sidelined” (Two Years On, Time To Pull the Douma ‘Gas Attack’ Out of the Memory Hole – Antiwar.com). By consistently foregrounding theories of staged attacks and OPCW malfeasance, Antiwar.com provided an English-language pipeline for the White Helmets “staging” narrative, helping it reach segments of the Western public that would mistrust anything coming directly from RT or PressTV.

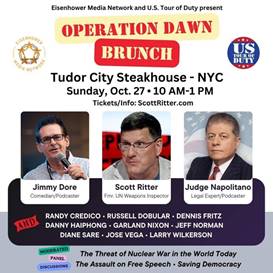

There is significant overlap in personnel and platforms that links Antiwar.com’s ecosystem with pro-Kremlin circles. Several frequent contributors to Antiwar.com have also appeared on Russian-friendly outlets or collaborated with pro-Assad media. For example, investigative journalist Gareth Porter – a longtime Antiwar.com writer – has repeatedly cast doubt on Syria’s chemical attacks and did so in alternative outlets often praised by Moscow. Even Antiwar’s staff acknowledge alignment with other alt-media sceptics: in 2024 its news editor Dave DeCamp was co-awarded the inaugural Pierre Sprey Award (funded by Ben & Jerry’s co-founder Ben Cohen) alongside Grayzone founder Max Blumenthal (Antiwar.com News Editor Dave DeCamp wins Pierre Sprey Award for DefenceReporting and Analysis! – Antiwar.com Blog)

Ben Cohen, co-founder of Ben & Jerry’s, has provided significant financial support to the Eisenhower Media Network (EMN) through his nonprofit organization, People Power Initiatives (PPI). Cohen serves as the president of PPI and has contributed over $1 million to the organization via the Ben Cohen Charitable Trust (The Daily Beast). EMN, a project under PPI, comprises former military, intelligence, and national security officials who often critique U.S. foreign policy, including opposition to military support for Ukraine. We can see from the event shown before a big crossover between our earlier reports and featuring a number of Larouche, Russian and Iranian media and LASG aligned speakers.

https://www.thewashingtonoutsidercenter.org/small-clues-big-networks-how-minor-details-exposed-a-web-of-extremist-affiliations-of-the-larouche-movement/

The Grayzone is notorious for defending Assad and attacking the White Helmets, yet here its editor and Antiwar’s editor were jointly feted for “clear-thinking and courageous” reporting – underscoring how these ostensibly disparate actors form a mutually-reinforcing network. In fact, Cohen’s charitable trust has been a financial backer of the Randolph Bourne Institute, donating to Antiwar.com’s parent organization. Thus, via well-meaning philanthropists like Cohen (a prominent opponent of U.S. wars), resources flowed to platforms that, in practice, serve Kremlin disinformation goals. This irony highlights the complex layering of the disinformation ecosystem: state propaganda benefits from partnerships with alternative media figures who may sincerely oppose war but end up echoing regimes that wage it.

The involvement of VIPS and Antiwar.com in Syria narratives demonstrates how reflexive control and Temnyk-style coordination extend into Western alternative media. By writing open letters and articles that sow doubt about Assad’s responsibility, these actors introduced friction into Western policy debates – exactly as Moscow intended. Russian officials even gloated that segments of Western publics and alt-media “picked up their Douma narrative,” achieving the goal of “muddying the waters” of perception. In propaganda terms, VIPS and Antiwar.com functioned as force-multipliers for the Kremlin: they translated and reinforced Moscow’s messages under the guise of independent Western voices. Disinformation was not only broadcast by state-controlled outlets, but also laundered through sympathetic NGOs, ex-officials, and alternative media. The White Helmets were thus attacked from all sides – via Russian and Iranian channels on one hand, and via Western dissident media on the other – in a coordinated attempt to deflect blame from the Assad regime. By the time these narratives circulated back into mainstream conversation (sometimes even cited by pundits or politicians), they carried the imprimatur of legitimacy. The case of VIPS and Antiwar.com shows how easily a false story can leap from a Kremlin Temnyk into Western discourse, blurring the line between genuine scepticism and manufactured doubt. It underscores that in today’s information wars, credibility can be weaponized – even retired spies and peace activists can become unwitting agents in a reflexive control campaign when their contrarian instincts align with an authoritarian regime’s agenda. The result is a highly effective form of narrative laundering that complicates the public’s search for truth amidst the fog of Syria’s war. (Syria’s Chemical Weapons: Assad Not to Blame, Say Truthers | The New Republic)

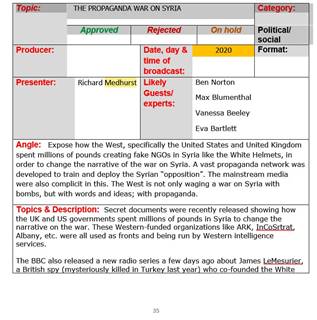

11. The PressTV Playbook: Internal Documents and Alt-Media Allies

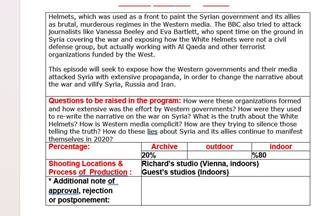

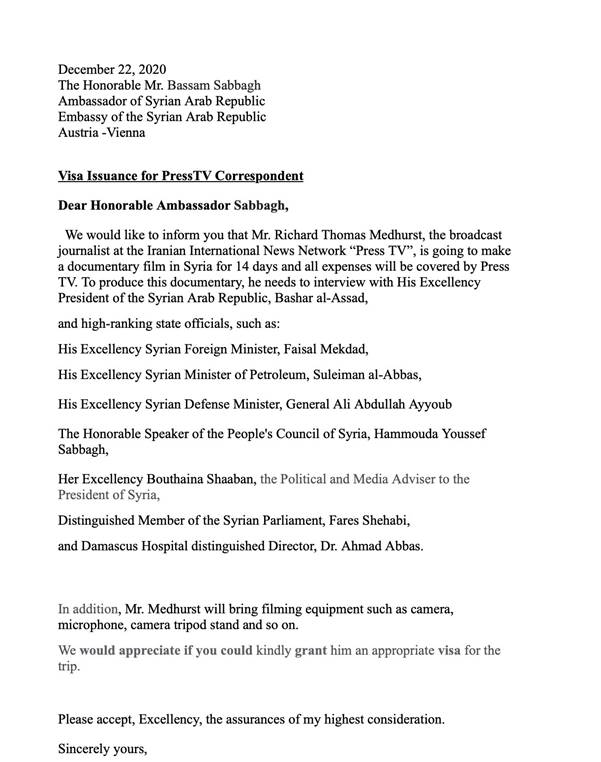

The leaked PressTV files offer a rare peek behind the curtain of how Iran’s state media planned and executed these propaganda campaigns – effectively, their playbook. In particular, an episode brief for a PressTV program (hosted by UK-based presenter Richard Medhurst) lays out the blueprint for an entire show dedicated to Syria’s “propaganda war.” The document lists the topic as “the propaganda war on Syria” with an angle to “expose how the West, specifically the United States and United Kingdom spent millions of pounds creating fake NGOs in Syria like the White Helmets, in order to change the narrative of the war on Syria.” It bluntly states that “The West is not only waging a war on Syria with bombs, but with words and ideas; with propaganda.”. This is remarkable for two reasons: first, it encapsulates the core propaganda message (accusing the West of doing exactly what the Russian-Iranian side was doing), and second, it shows the premeditated nature of the content. The narrative was set from the start – the White Helmets were to be depicted as a fake NGO, part of Western information warfare – and the program was built around proving that thesis.

Even more telling is the list of “Likely Guests/experts” invited to this show: Ben Norton, Max Blumenthal, Vanessa Beeley, Eva Bartlett. All four are well-known figures in the alternative media sphere who have echoed pro-Kremlin and pro-Assad lines. Blumenthal and Norton run The Grayzone, a site that has repeatedly attacked the White Helmets and defended the Syrian government’s narrative. Beeley and Bartlett, as discussed, built their personas around alleging White Helmet conspiracies. The fact that PressTV’s producers corralled these same voices is not a coincidence; it exemplifies the symbiosis between state propaganda outlets and fringe “alt-media” allies. In other words, the people presented to audiences as independent journalists or experts were, in reality, deeply embedded in the Russia-Iran information ecosystem or even in the case of Richard Medhurst – directly employed by them.

This coordination with alt-media serves a strategic purpose. State outlets like RT or PressTV can reach a wide audience, but some viewers distrust anything from a “state media” label. By featuring Westerners who run their own blogs or YouTube channels, they add a patina of grassroots credibility to the narrative. It creates a pipeline: conspiracy theories might germinate on fringe websites, get picked up by PressTV in a polished segment, which is then cited by other fringe blogs as “even Iran’s TV confirms…” and so on – a circular amplification loop. The PressTV playbook document also referenced how the BBC (a Western outlet) had aired a radio series about James Le Mesurier, the White Helmets founder, and how that BBC program criticized people like Beeley and Bartlett. PressTV’s plan was essentially a counterattack: to use those very people (Beeley, Bartlett) to turn the tables and claim it was the BBC and the West engaging in propaganda, while painting the White Helmets as frauds. This shows a keen awareness of the information battlefield – the Iranian producers watched what the other side was saying and strategized responses accordingly, blending facts with propaganda.

In sum, the internal PressTV materials reveal an active, deliberate shaping of content – topics chosen, narratives decided, guests hand-picked to reinforce the message – all under the supervision of state censors (since each episode needed approval). It’s a case study in how state propaganda doesn’t operate in a vacuum but intersects with a broader network of sympathetic voices. By the time such a PressTV episode aired, it was less a piece of journalism and more a scripted drama, casting the White Helmets as villains, the West as puppeteers, and the alt-media personalities as truth-tellers under fire. It is deeply ironic – and telling – that a show ostensibly about “exposing propaganda” was itself a product of an elaborate propaganda design, one coordinated between nations and across media platforms.

12. Psychological Warfare: Undermining Humanitarian Witnesses

Why go to such lengths to attack a group of rescue volunteers? The answer lies in the psychological and strategic impact that witnesses like the White Helmets have in a conflict. The White Helmets were not just rescuers; they were also documentarians of the Syrian war’s carnage. Armed with GoPro cameras and smartphones, they captured images of bombed-out hospitals, wounded children, and scenes of destruction that directly contradicted the Syrian government’s narrative. In essence, they were witnesses under fire in both the literal sense (bombs falling as they worked) and the figurative sense (targeted by information warfare). The propaganda campaign against them was designed to neutralize their testimony. This is a classic psychological warfare tactic: destroy the credibility of the witness so that their testimony (in this case, video evidence and reports) will be doubted or dismissed.

One tactic used was dehumanization and demonization. By branding White Helmets as “terrorist affiliates” or “agents of Western regime-change,” propagandists tried to flip the moral script. Instead of sympathy for these brave volunteers, the audience is nudged toward suspicion or even hatred. When a White Helmet appeared on screen in news footage, someone primed by propaganda might think, “Are they really saving people, or is this person staging this rescue?” This seed of doubt is extremely powerful. It not only tarnishes the White Helmets’ image, but can also sap the morale of those who support them. Even the volunteers themselves could become demoralized if they know they’re being widely maligned as terrorists – a cruel psychological blow to people risking their lives to help others. In fact, some White Helmets reported that such smears made their dangerous work even heavier to bear, as they felt they had “targets on their backs” not just from bombs but from character assassination.

Another psychological tactic was projection – accusing the White Helmets of crimes that the Assad regime or Russia were themselves accused of. This creates confusion and a false moral equivalence. If every side is accused of atrocities and lies, an average person might throw up their hands and conclude “truth is the first casualty of war” and tune out. That cynicism is exactly what propagandists want, because it means war crimes can occur with less outrage. By muddying the waters, they aim to induce a kind of compassion fatigue or scepticism in international audiences. It’s psychologically easier for people far away to stop caring if they’re told that those suffering (or those helping the suffering) are not innocent. Indeed, Russian and Iranian media hammered the notion that White Helmets only operated in “terrorist-held areas”, subtly suggesting that all those civilians they saved were themselves somehow complicit or not worth Western pity. This guilt-by-association blunts the emotional impact of the harrowing scenes the White Helmets disseminated. If viewers subconsciously think “those victims are from the terrorist side,” they may feel less empathy, which again serves the regime’s interests.

Finally, let’s consider the intimidation effect. The phrase “witnesses under fire” can apply not just to the White Helmets but to anyone who might speak out about atrocities. By vilifying the White Helmets so publicly and relentlessly, the Syrian regime and its backers sent a message to other potential witnesses: you too can be destroyed in the media if you cross us. Doctors who treat chemical attack victims, journalists who report from rebel areas, defectors who carry evidence – all could look at what happened to the White Helmets and think twice. This is psychological warfare at a broad level: using one high-profile target as an example to instil fear and silence others. In conflict zones, information is power, and those who carry information (witnesses) become threats to those who want to control the narrative. The assault on the White Helmets’ credibility thus served as a warning shot to many others. Despite this, the White Helmets continued their work and continued filming – a testament to their courage. But there is no doubt that the propaganda barrage took a toll on how their work was received globally. It is a sobering illustration of how state propaganda can undercut even the most clear-cut humanitarian virtues, turning hope and heroism into doubt and cynicism through sheer force of narrative.

13. Propaganda, Perception, and the Battle for Truth

The saga of the White Helmets in Syria’s war reveals a much larger story about modern propaganda and its ability to distort reality. In dissecting how Russia and Iran coordinated to undermine this rescue group, we’ve seen classic techniques of state influence – reflexive control, Temnyk-style messaging, conspiratorial framing – applied in a very contemporary way. This was not propaganda through clumsy slogans or obvious censorship, but through a sophisticated weaving of fact and fiction, leveraging every medium available: TV reports with authoritative voice-overs, social media posts, YouTube documentaries, and even stunts on the international diplomatic stage (Roger Waters or Jackson Hinkle appearing at the UN). The campaign’s success can be measured in part by the doubt and division it sowed. To this day, there are corners of the internet where the White Helmets are reviled as villains, where any footage they release is assumed fake. That represents a win for the propagandists, because it means fewer people unequivocally trust evidence of the Syrian regime’s atrocities, and the global consensus against those atrocities is weakened.

What makes this case especially noteworthy is the joint effort of two state actors – Russia and Iran – working in concert. This kind of propaganda synchronicity across borders points to an evolving model of information warfare. Authoritarian regimes, often accused of severe abuses, have learned that banding together in the info-war can bolster each other’s narratives and lend them an air of broader legitimacy. Moscow’s lies were echoed by Tehran, and vice versa, creating a multi-front assault on the truth. It’s a strategy of “internationalizing” propaganda: if many outlets in different countries say the same thing, a casual observer might assume it’s true (or at least there’s a controversy). The White Helmets found themselves at the nexus of this strategy, and thus suffered relentless attacks. And while our focus has been on Syria, the blueprint uncovered here – of narrative coordination and mutual amplification – is likely being employed elsewhere, whether it’s about conflicts in Ukraine, misinformation on global health, or other geopolitical flashpoints.

Yet, understanding these tactics is the first step to countering them. By bringing internal documents and direct quotes to light, we peel back the layers of the narrative and expose how it was constructed. We see that what appeared to be a grassroots wave of doubt about the White Helmets was in fact a manufactured narrative, propagated by state media professionals and their partners. Terms like “so-called humanitarian group” did not emerge organically; they were seeded. The harrowing charges of organ trafficking and staged attacks were not born of genuine investigative journalism, but of strategic deception. Recognizing this helps restore the factual record: that the White Helmets were, despite any imperfections, a genuine civil defence organisation that saved lives and bore witness to suffering. It also reminds us to critically evaluate information, especially when it seems to discredit those who expose atrocities.

In the end, the story of “Witnesses Under Fire” is a cautionary tale of the power of propaganda. It teaches us that truth alone isn’t enough to win the narrative war; truth needs champions and careful presentation, lest it be drowned out by a flood of coordinated lies. As we navigate a world where such information operations are increasingly common, the experience of the White Helmets underscores the importance of supporting independent verification, protecting frontline witnesses, and fostering media literacy among the public. Only by doing so can we ensure that genuine heroes are recognized as such, and that the broader strategies of state propaganda do not succeed in rewriting history in real time. The battle for truth is ongoing, but by shedding light on how the falsehoods were crafted, we arm ourselves to better defend against them in the future.

No responses yet