by Irina Tsukerman

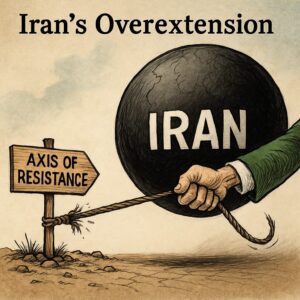

Why the Axis of Resistance is Likely not going anywhere, though it may change brand, flavor, or members.

The false dichotomy between the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafist networks, on the one hand, and the Iran-backed Shia “Axis of Resistance” is easily dispelled even after a cursory glance at the long history of cooperation between fundamentalist Sunni and Shia networks.

Iran-Al Qaeda Connections

While the history of joining forces against external threats or targets goes back centuries, as the co-author of this paper, Irina Tsukerman, has written previously, the Khomeinist regime in Tehran took the cooperation with the Muslim Brotherhood to the next level, translating and disseminating texts [1] and engaging in intellectual and political alliances for decades. Al Qaeda, a jihadist off-shoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, had tactical ties with Iran going back to the Sudan meeting with Osama bin Laden in April 1991. [2] Since then, their coordination only blossomed, with Al Qaeda reportedly receiving Iran’s support in the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Later, one of its leaders, Saif Al-Adel, found refuge in Iran. [3] In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, Iran worked with the International Office of the Muslim Brotherhood’s London Office to organize interfaith meetings between Sunni and Shia Islamists to resolve ideological impediments to increased cooperation. [4] For political and pragmatic reasons, both the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood strove to hide their nexus, ideological similarities, support for revolutionary rhetoric and approaches, and collaboration on anti-Western campaigns by clouding joint activity in an aura of “secrecy and ambiguity” [5] for decades. The history of cooperation and underlying ideological conflicts are undeniable despite occasional conflicts and divergent dogma.

Iran Adopts Muslim Brotherhood Off-Shoots into the Axis of Resistance

More recently, Iran backed old Muslim Brotherhood daughter organizations, such as Hamas, incorporating them into its anti-Israel and anti-Western “Axis of Resistance”. However, the integration of operations went beyond political backing, training, and funding Hamas, participating in the planning of terrorist operations, or even promoting Hamas propaganda in the Middle East and in the West [6]. In the post October 7 world, after the war in Gaza broke out, Iran extended its cooperation beyond working with Hamas operatives and relied on Muslim Brotherhood networks in Jordan to smuggle weapons to destabilize Judea and Samaria (West Bank) and the Hashemite Kingdom itself. [7]

However, the Islamic Republic’s efforts to breach the historic suspicions in the Arab and Sunni world go far beyond its links to the largely reviled Ikhwan, which despite its periods of waxing and waning in various parts of the Muslim world, successfully staging uprisings, assassinating leaders, infiltrating key institutions, and having a disproportional impact on public affairs, remains relatively a minority overall. Indeed, Iran in fact, sought to cement its hold in the Muslim world—with the goal of displacing Saudi Arabia as the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques [8]—and exporting the Islamic Revolution, by building bridges even with apparent ideological foes, the Salafists. [9] Iran has cynically used Salafist jihadists as a bulwark against Western influence in Iraq.

For instance, it has exported and encouraged Salafist jihadists, including some who eventually became ISIS affiliates, to travel to Iraq and join forces with their counterparts in Mosul and other areas hoping to turn Iraq into a “new Vietnam” for the United States. [10] A logical conclusion to the analysis of Iran’s support of Al Qaeda in the events leading up to 9/11 is that this form of cooperation would not have been possible without the participation of—and served as a bridge to—the nexus of Salafists and Muslim Brotherhood in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and other parts of the Middle East. Former Secretary Pompeo described Iran as a “new home base” for Al Qaeda, and underscored that the relationship spans nearly 3 decades, referencing the 9/11 Commission Report. [11] The relationship, as mentioned before, was handled via Osama Bin Laden, who formally forged these ties in Sudan.

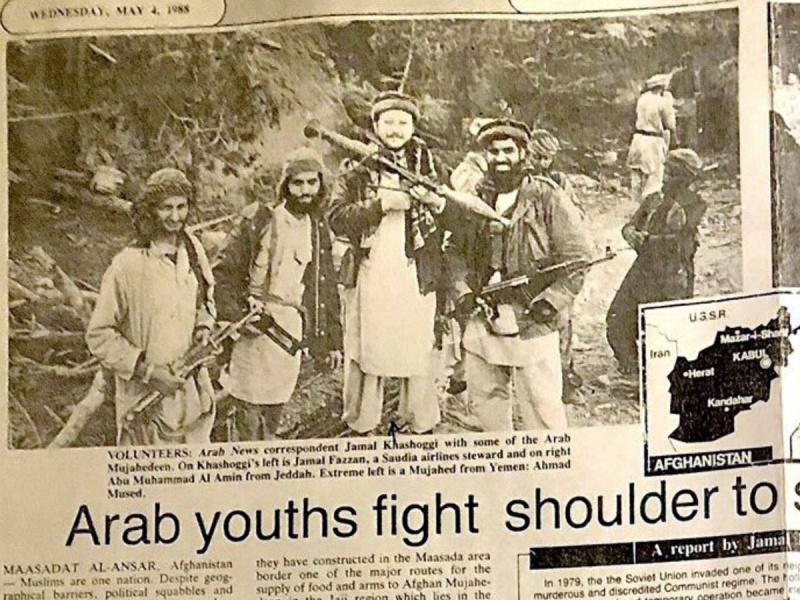

Osama bin Laden maintained his relationship with Salafist ad Muslim Brotherhood backed officials in Saudi Arabia, including Prince Turki Al Faisal, who had served as an Ambassador to London and who during that period was Saudi Arabia’s Director of General Intelligence, via Jamal Khashoggi, who had also later worked as Turki Al Faisal’s executive assistant at the London Embassy. That relationship goes back to when Khashoggi—an intelligence officer at one point [12]—was embedded under a journalistic cover with the anti-Soviet mujahedeen in Afghanistan, who included Osama bin Laden (at the time widely lauded as a “freedom fighter” or “peace warrior”). [13][14]

Saudi Old Guard and Islamic Republic Policy Mouthpieces in the West Forge a Bond

Years later, Turki Al Faisal’s outreach to the Iranian American Obama administration official Arianne Tabatabai, who notoriously was named as part of Iran’s influence operations network in Washington DC, was approved by senior officials in Iran. [15] Curiously, Seyed Hossein Mousavian, the Former Ambassador of Iran to West Germany, rumored to be the Iranian intelligence Director of Operations, at the time of the assassination of the Iranian Kurdish opposition activists at the “Mykonos” restaurant, [16] and who often acts as an informal Islamic Republic representative to the United States, vocally applauded the prospects for Iran-Saudi normalization, despite the long-standing cultural and historic distrust between the two countries. [17]

Since December 2020, after his surprise appearance at the Manama Dialogue conference where rather than focusing on the advancement of the Abraham Accords, he railed about the Palestinian cause [18], Turki Al Faisal returned to the public scene, publishing a new book which provides a distorted narrative about the role of the Arab mujahedeen in Afghanistan [19], and appearing with increased frequency as a spokesman for Saudi foreign policy at home and at various events in the US.

Post Al-Ula Agreement, Qatar Becomes a Bridge Between Sunni and Shia Islamists

Following the Al Ula Agreement, which normalized Saudi, Emirati, Egyptian, and Bahraini relations with Qatar, and following the Iran-Saudi normalization, the Old Guard network of Salafists and Muslim Brotherhood supporters within the Saudi royal family not only reemerged to the forefront but appeared increasingly and publicly at ease with Iran. One example of that proximity appears to be a hostile, seemingly coordinated statement issued by Iran, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia in response to the Al Aqsa Flood Operation (the Hamas-led terrorist attack on Israel), which blamed Israel for the situation and issued no sympathy to the Israeli victims of terror. [20] Prior to that, Saudi Foreign Ministry statements were already using increasingly harsher rhetoric against Israel, referring to it as “the Occupation Power” during the April 2023 Ramadan riots by the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Some believe that Qatar [21] – and perhaps some of these pro-Islamist or Salafist officials in Saudi Arabia – likely knew some details about the terrorist attacks in advance.

Doha was accused of lending assistance, by providing Hamas with funding and with various forms of equipment, such as the paragliders used by Hamas in the initial stages of the attack. Islamist and Salafist forces certainly stood to benefit from this attack. A recent Saudi military visit to Iran [22] right after the reelection of Donald Trump, who appears to be hawkish on Iran and its proxies, and amid a military pressure campaign on the Axis of Resistance, which included assassinations of proxy leaders, and a major Mossad pager operation which severely weakened Hizbullah, raised questions about the direction of Saudi foreign policy and its strange proximity to Tehran when the Islamic Republic appeared to be growing weaker by the moment.

Iran Benefits from the Qatar-Turkey Axis

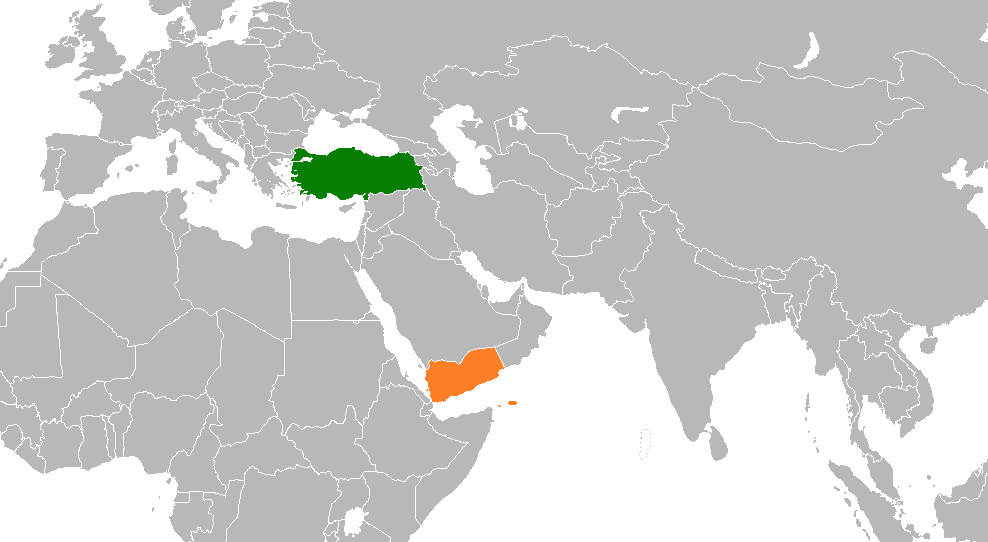

Considering these developments, the Saudi posture in the Levant – such as the quick recognition of the Turkey and Qatar-backed HTS-led transitional government in Syria, which includes defense talks with Saudi Defense Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman in Riyadh [23], followed by a consequent meeting between HTS leader (later, President of the Syrian Unity Government) Ahmed Al-Sharaa and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and continued relations with Iran, should be less surprising and should appear less contradictory than what conventional wisdom would posit. Iran’s increasingly overt ties to Saudi and other Salafist and Muslim Brotherhood networks ensure the preservation, rather than a radical shift, in the geopolitical status quo in the Middle East. Iran’s growing closeness with Qatar [24] guarantees that the Tehran regime will benefit from a prospective Qatar-Turkey pipeline which is now a strong possibility in Syria [25]. Iran and Qatar share a major gas field, and either route considered for implementation would include and benefit Saudi Arabia.

Thus, while formally Iran has lost ground in Syria, informally, and by default, Doha opens its doors to Damascus. Both HTS and Turkey are desperate for the financial benefits of an effective energy cooperation framework, but Qatar’s co-dependency on Iran means that behind the scenes the Islamic Republic will retain influence and entry into Syria. While Erdogan may wish to take over sponsorship of Hamas and transfer of weapons to Judea and Samaria for Iran, he will likely continue cooperate with Tehran over issues such as blocking Kurdish autonomy in Syria and Iraq, or even allowing the passage of Iranian weapons to Lebanon – for a price. In exchange, Iran will focus on strengthening its hand in Iraq.

To accomplish that goal, the drawdown of NATO forces in Iraq should be maneuvered so that the US remnants in Iraq are ambushed and surrounded. The isolationist-leading Trump administration is ideal for pushing such a game plan. To accomplish its goal, Iran benefits from the renewal of its notorious strategy, of utilizing Salafists to destabilize Iraq and to entrap the US in an impossible security situation. Already the US is not benefiting economically from its presence in the country infamous for its corruption and parochial approach to foreign investments. A major outbreak of violence, which could attract scores of ISIS and other jihadist groups back to Mosul and in return, strengthen the old of the Iran-backed Shi’a militias would be a nightmare scenario. There is evidence that a precursor plan for such an operation is already in the works—and once again, would not be possible without a hand from the Salafist and Muslim Brotherhood networks in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Qatar.

The Plan to Turn Iraq into a No-Go Zone for Americans Hinges on a Promised Golden Parachute

The Iran-Salafist/Muslim Brotherhood strategy for entrapping the US in Iraq involves the rekindling of Sunni armed resistance, with Turkey fronting the operation politically, while Qatar and the Saudi Old Guard networks take care of the funding behind the scenes. Turkey’s pro-Muslim Brotherhood President Erdogan consistently plays the neo-Ottoman card rhetorically, advancing the HTS-led takeover of Damascus with the help of Turkish intelligence and vowing to restore the former Ottoman-controlled territories as Turkish spheres of influence from Syria to Libya and perhaps beyond. However, with inflation through the roof and the Turkish lira in freefall, such a campaign is hardly possible without foreign assistance from the likeminded.

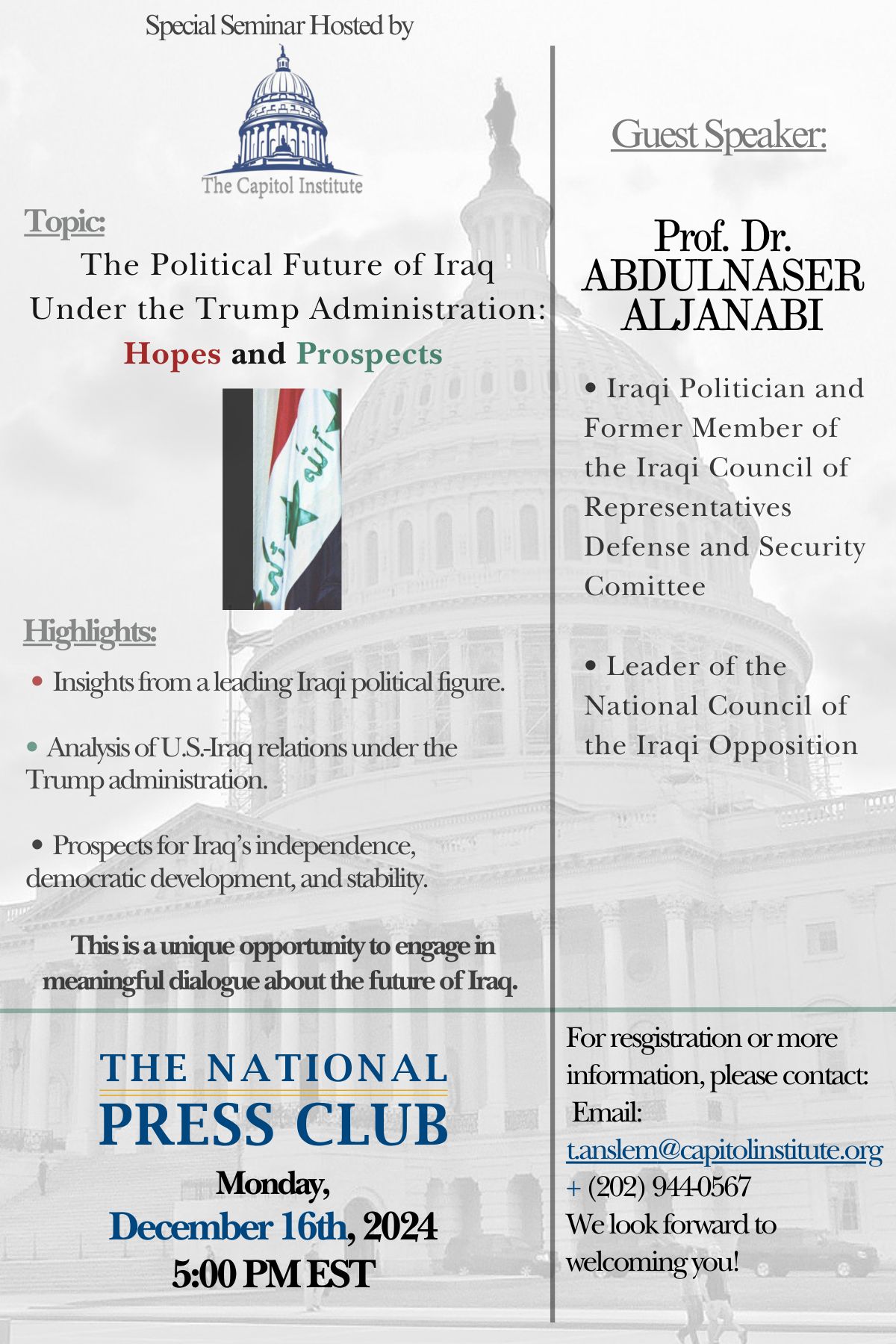

Turkey’s pivot to the Gulf States ensures sufficient backing for both the military and information domain influence operations. A recent event organized by The Capitol Institute at the National Press Club in Washington DC illustrates the precise approach for engaging public opinion in the relevant pro-Trump policy circles. [26] The speaker was Professor Abdul Nasser Al-Janabi, the chairman of the National Council of the Iraqi Opposition. Al-Janabi [27], known for his Salafist views, once took part in armed resistance in the years 2003-2013, before fleeing the country. The Iraqi government sent a Red Notice for al-Janabi to the Interpol, which would be enforceable in the United States [28]. The Capitol Institute, in effect, circumvented an international search warrant on a designated terrorist, by hosting him via Zoom from his current outpost in Turkey.

Capitol Institute Bypasses Interpol Red Notice By Bringing a Jihadist to Washington – via Video

Once elected to the Iraqi Council of Representatives for the Sunni Arab-led Iraqi Accord Front, al-Janabi had his parliamentary immunity lifted after being charged with kidnappings and terrorism. In 2013, Al-Janabia was sentenced in absentia to a life sentence in prison for his terrorist activities by the Iraqi Central Criminal Court. [29] Al-Janabi is alleged to have been part of Al-Zarqawi’s network of former Baath party members, many of whom later formed ISIS. The network, called the “Tawhid and Jihad Islamic Group” had extensive ties to Syria and Iran, further underscoring the fluid ties between Salafists and the Khomeinist regime and its regional allies. [30] Al-Janabi also appears to be connected to other former lawmakers alleged to have been responsible for waves of violence and thuggery, including suicide blasts. [31]

Al-Janabi’s presentation, directed via a question-and-answer session with The Capitol Institute’s Maria Maalouf, focused on the future of Iraq-US relations under the Trump administration. Al-Janabi’s position, which was translated from Arabic by The Capitol Institute-affiliated interpreter, can be summarized as follows:

- The major problem with the Iraqi government is corruption

- Al-Janabi’s National Council of the Iraqi Opposition opposes the current Iraqi constitution (as al-Janabi has maintained since 2005) and wants to see it tossed out

- Al-Janabi favors a secular centralized federal government, which protects the rights of all citizens on the ethnic basis but opposing autonomy for Kurds.

- Al-Janabi views Iran’s role in Iraqi politics as a threat and is sending a message to the Trump administration, promising oil and gas-related concessions to the US in exchange for political support and backing that could bring the National Council of Iraqi opposition to power, despite Al-Janabi’s coalition, which consists of approximately 70 civil society Sunni Arab organizations, is in the minority of about 150,000 followers compared to the current Shia majority in Iraq.

If actualized, and despite his lip service dedication to secularism, Al-Janabi appears to envision a new version of a Saddam Hussein apartheid Iraq, where the Sunni Arab minority held centralized power.

Given that in addition to being a former lawmaker, Al-Janabi, who perceives himself as a leader of this moment, is also a Salafist cleric, it is far more likely that such a state would lean towards a Salafist/Islamist governance, like Hussein’s Iraq in later years, than towards secularism. Given the fate of the Kurds under Hussein, their support for a project where self-governance is out of the question in any form, is highly unlikely.

The Usual Games: Salafi-Jihadists in Sufi Clothing

During the program, Al-Janabi denied being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood or ISIS, and claimed to be a practicing “Naqshabandi Sufi”. A cursory search, however, reveals a strong connection between the so-called Naqshbandis and Salafist organization. The Naqshbandi-Khalidi order forms the core of political Islam groups in Turkey, dating back to its reputation of the dawa (dissemination of Islam) of the Ottoman Empire, and its compatibility with Orthodox Islam movements, such as Salafism.[32] There is a documented history of Ex-Baathists turning to Naqshabandi Sufis, to legitimize insurgency. Some of these groups took up arms along other Sunni jihadists in Iraq in response to the hanging of Saddam Hussein. [33]

At best, by not mentioning his Salafist affiliation, al-Janabi was being coy. At worst, borrowing from the Muslim Brotherhood adaptation of the Shia concept of taqiyya [34], al-Janabi betrays his deliberate deception and manipulation of his audience, playing on their ignorance. In regions recently susceptible to the spread of Salafism thanks to the Turkey and Gulf dawa, such as Central Asia, Salafi movements use the Naqshbandi Sufi cover to reach local populations far more accustomed to Sufism. [35] Al-Janabi was acting not in isolation but in accordance with a tradition masking true aims behind a palatable appearance.

During audience questions, author of this article Irina Tsukerman, asked Al-Janabi: “There is a long record of the US committing to support various opposition movements only to discover that they are no better than or even worse than whatever came before. In this age, when Shi’a can pretend to be Sunni, Muslim Brothers can pretend to be secularists, and Salafists can pretend to be Sufi, how can the US administration trust a resistance movement or an opposition group and ensure the veracity of its promises?” Al-Janabi, as seen from the aforementioned video, did not directly answer the question, nor did he acknowledge the point about deceptive practices, but reiterated commitment to working with the Trump administration and repeatedly blamed Iraqi government corruption and the inadequacies of the Iraqi constitution for all the problems.

Al-Janabi: A Small Piece of a Much Bigger Puzzle

Irina Tsukerman’s conversation with The Capitol Institute’s Maria Maalouf, a journalist originally from Lebanon, after the event was revealing. Maalouf denied she was advancing Al-Janabi’s political platform and insisted that she was only doing her job as a journalist by asking the speaker questions about his views. She indicated that the real purpose of the event was to open the conversation with the American policy watchers. Maalouf underscored that in the discussion, al-Janabi sent several messages to the administration, making a direct appeal for future cooperation, and that his staffers were likely already having such discussions with Donald Trump’s transition team, regardless of what transpired at the National Press Club.

Still, there appears to be more to the story. Maalouf explained she met Al-Janabi’s cohorts at the last Trump campaign Michigan event with the Muslim leadership, where she was approached by these associates of the National Council because she was an Arabic-speaking journalist. Maalouf explained that Al-Janabi was working with a tight circle of associates. These associates include Muhammad Nassir Sadoun Al Jabouri, an “ex”-Baathist surgeon and municipal official in Iraq [36] and Habat al-Halbusi, the chair of the Parliament Oil and Energy Committee in Iraq [37], notorious for threatening to kill a critic of the energy services in Iraq, along with others who appear to be part of an energy cabal plotting to gain the Trump administration’s support in exchange for future oil concessions. If this is how the event came to pass, it raises serious questions about the vetting process and counterintelligence capability of the Trump campaign and transition team.

Ankara’s Game Plan Revealed, and It Relies on Saudi Old Guard Support

Maalouf revealed Turkey is providing extensive financial support to the National Council for Iraqi Resistance, and has strong lobbying links in the United States, to the tune of $10 billion. She added Turkey aims to repeat its success in Syria, in Iraq soon, indicating a plot to united armed factions and to force the current Baghdad government out of office, displacing it with a Sunni Arab coalition. From the conversation, at least some Saudi factions are on board with the plan and see a future in supporting Al-Jabani’s campaign for legitimacy in the US. However, the Trump administration will see no value in active US ground troop engagement in any military kerfuffle in Iraq. Such an uprising would result in massive mobilization of the government forces in Iraq and the Shia militias.

The only logical outcome to such an adventure is widespread bloodshed and general instability. Who is best served by such a doomed uprising? Clearly, Iran gains an opportunity to reclaim ideological ground and to strengthen its present; assorted terrorist organizations would likely flock inwards to join the fray, possibly spilling over the border to Syria and contributing to the resurgence of ISIS, and the return of the Salafist-jihadist and Muslim Brotherhood ideology to the forefront, the US presence will be marginalized and possibly withdrawn altogether, particularly if the current Trump team as nominated is in place at the time these events happen, and the Saudi and Turkish Islamist and Salafists gain ground in the region.

Turkey gets to assert its presence even more in Northern Iraq, which it claims as part of the Ottoman legacy, working with Iran to crack down on Kurdish role in the area and to break up the unification between Iraqi and Syrian Kurdish forces. The Saudi elements benefit by advancing their relationship with Iran and by weakening the US influence in the region. As facilitators of the Iran-backed regional mayhem, they will be well positioned to monopolize any future governance and economic projects in Sunni Arab regions and strengthen economic cooperation with Iran and Turkey—at the cost to everyone else.

Indeed, consequent developments have lifted the veil over the new Muslim Brotherhood expansion plan – part and parcel of Turkeye-driven revitalized geopolitical strategy for the MENA region. Consequent events revealed that The Capitol Institute discussion was not an isolated incident, but rather, a reflection and a part of a cohesive regional strategy already being implemented into action.

A Possibility of a Yemen-Syria Fundamentalist Axis Arises [38]

The recent announcement of the “Change and Liberation Movement” in Seiyun, Hadramaut Governorate, marks a significant development in Yemen’s complex political landscape, which is currently defined by fragmentation, sectarianism, and a prolonged civil war. This movement, led by former al-Qaeda leader Abu Omar al-Nahdi, represents an attempt to reshape Yemen’s political future through a populist platform focused on reform, justice, and independence. To understand the broader implications of this development, it is crucial to explore both the background of the movement and the complex political, security, and social dynamics shaping Yemen today.

The Emergence of the “Change and Liberation Movement” [39]

The declaration of the “Change and Liberation Movement” signals a pivotal moment in Yemen’s post-war evolution. Yemen, which has been embroiled in a devastating conflict since 2014, faces a fragmented political environment characterized by multiple competing factions, each with their own ideological and territorial ambitions. The movement’s founding statement emphasized a desire to address the “loss of homelands” and the pressing need for survival amidst a collapsing state structure, pointing to widespread dissatisfaction with the ongoing war and the failure of various political actors to deliver stability or reform.

At its core, the movement seeks to offer a pragmatic vision of change—a sharp contrast to the theoretical posturing and political deadlock that have plagued Yemen’s transition since the Arab Spring of 2011. By stressing that “change is not created by slogans but by will and practical steps,” the movement positions itself as a realist political entity focused on achievable goals, rather than ideological pursuits. This pragmatic stance could resonate with Yemenis weary of war and disillusioned with the ineffectiveness of existing political institutions.

Leadership and Historical Context

The movement is led by Abu Omar al-Nahdi, a former al-Qaeda leader who defected from the organization in 2018. His history within al-Qaeda, especially his involvement in the Iraq conflict and ties to Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa, adds layers of complexity to his new political role. His leadership could be seen as part of a broader trend within the region, where former insurgents and fighters are transitioning into political figures in an attempt to influence the post-conflict political order.

Al-Nahdi’s shift from militant to political leader underscores a critical aspect of the movement’s appeal: the maturation of political engagement over militant tactics. In his speech, he emphasized that his movement would focus on practical steps for reform, rather than continuing the destructive cycles of violence that have marred Yemen for decades. His rejection of slogans in favor of action suggests a shift toward a more realistic and institutionally grounded approach, which might appeal to Yemenis who have grown frustrated with the country’s incessant conflict.

However, al-Nahdi’s past ties to al-Qaeda are likely to complicate his political ambitions. His former association with one of the world’s most notorious terrorist groups could alienate certain segments of Yemen’s population, particularly those in areas where al-Qaeda’s extremist agenda has been most active. While his defection may signal a willingness to abandon violent extremism, it remains to be seen whether Yemenis, especially those who have suffered from the actions of groups like al-Qaeda, will accept him as a legitimate political leader. This challenge underscores the difficulty of transitioning from armed rebellion to political legitimacy, particularly in a context as fractured as Yemen’s.

The Movement’s Strategic Objectives

The movement’s three core objectives—comprehensive reform, state-building based on justice and efficiency, and the protection of rights and freedoms—reflect a commitment to addressing the root causes of Yemen’s political and social malaise. These goals mirror long-standing demands from the Yemeni population, particularly those in the South, who have called for better governance, social justice, and an end to the corruption that has plagued the country for decades.

Yemen’s long-running conflict has been exacerbated by corruption and mismanagement, both by the Houthi terrorist movement (“Ansar Allah”) in the North and the internationally recognized government in the South. The movement’s emphasis on combating corruption aligns with the popular desire for greater accountability and transparency in government.

Yemen’s institutions have been severely weakened by years of conflict. The movement’s call for the rebuilding of state institutions is critical to any lasting peace and stability. Its focus on creating a modern state grounded in justice and efficiency suggests a recognition of the need to reform Yemen’s political apparatus to meet the needs of its citizens, which is crucial for the country’s post-conflict reconstruction.

In a country where rights abuses have been rampant, especially during the war, the movement’s pledge to protect freedoms and social justice is a compelling vision that could appeal to marginalized groups, particularly women, youth, and civil society organizations who have been sidelined in the political process.

The Political Landscape and the Regional Context

The launch of the “Change and Liberation Movement” occurs at a time when Yemen’s political structure is deeply fragmented. The war between the Saudi-backed Yemeni government and the Iran-backedHouthi terrorists, coupled with the presence of various tribal, Islamist, and separatist factions, has created a complex web of competing interests. The movement’s desire to forge a new, unified national vision could be seen as an attempt to capitalize on the growing disillusionment with the war and the failure of traditional political forces to deliver meaningful change.

The movement’s adoption of non-violent, political means to achieve its goals sets it apart from other factions that rely on militancy and armed struggle. In a region where Islamist militias and separatist movements have long dominated the political discourse, the “Changing and Liberation Movement” seeks to provide a new path forward, one that prioritizes nation-building and reform over continued violence.

The international community, particularly the United States and the Gulf states, will likely take a cautious approach toward this new movement. While it may align with the broader regional desire to stabilize Yemen, the movement’s association with a former al-Qaeda leader may raise concerns about its credibility and ability to maintain regional and international support. The movement’s success in this regard will depend on its ability to separate itself from extremist factions and prove that it can be a force for positive change rather than an incubator for further violence.

The Road Ahead

The “Change and Liberation Movement” faces both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, its focus on pragmatic reform and justice could resonate with a population that has grown tired of corruption and warfare. Its emphasis on inclusivity—with a call to involve the people in decision-making—suggests a desire to forge a more participatory and transparent political system, which is vital for any lasting peace in Yemen.

On the other hand, the movement’s leader’s former ties to al-Qaeda and its emergence in a deeply fragmented political environment may hinder its ability to gain widespread support. If it cannot distance itself sufficiently from its extremist roots, the movement may struggle to gain the trust of both the Yemeni people and international actors.

Ultimately, the success of the “Change and Liberation Movement” will hinge on its ability to translate its principles into concrete actions that address Yemen’s political, social, and economic crises. If it can navigate the political complexities of Yemen’s post-war environment and foster broad-based support, it could become a key player in shaping the future of the country. However, its ultimate impact will depend on whether it can deliver on its promises of reform and governance, rather than simply offering another layer of political fragmentation in an already fragmented state.

Turkey’s involvement in the “Change and Liberation Movement” in Yemen, along with its broader regional strategy, reflects an intricate and evolving approach that mirrors its actions in Syria. Much like its support for factions opposing Bashar al-Assad in Syria, Turkey’s backing of this new political entity in Yemen serves its wider geopolitical interests. It emphasizes Ankara’s desire to shape the political order in the Middle East by supporting non-state actors that can advance Turkey’s strategic goals while undermining the established status quo. By backing movements like the “Changing and Liberation Movement,” Turkey appears to be aiming at creating a new political reality that aligns with its regional ambitions—much as it has done in Syria to reshape the balance of power in the Levant and assert itself as a pivotal regional actor.

Turkey’s Strategy in Syria: An Analogy to Yemen

To fully appreciate Turkey’s strategy in Yemen, it is essential to reflect on its interventions in Syria. Since the onset of the Syrian civil war, Turkey has actively sought to weaken the Assad regime, which it views as an adversary, while positioning itself as a key player in determining Syria’s post-war future. This approach was manifested in its military operations, financial backing, and political support for a broad range of opposition groups—including the Syrian National Coalition and the Free Syrian Army (FSA). The goal was to support these actors as alternatives to Assad’s rule, with the broader objective of remaking the Syrian political landscape and ultimately securing influence over its post-war reconstruction.

Turkey’s support for Syrian rebels, particularly in the early years of the conflict, was designed to undermine the central authority in Damascus and eventually force Assad’s downfall. In this way, Turkey’s involvement was a direct challenge to the existing political and military order in Syria. By supporting various opposition groups—ranging from secular rebels to more Islamist factions—Turkey positioned itself as a critical actor in the conflict, steering the direction of the war and seeking to prevent Iranian and Russian influence from solidifying in Syria, both of which have supported Assad.

Similarly, Turkey’s interest in Yemen seems to follow a parallel logic. Turkey has increasingly sought to carve out a presence in the Arab world, where it sees itself as a leader of a new political order that balances the influence of the United States, Russia, and Iran. The backing of the “Changing and Liberation Movement” fits within this broader strategy. Just as Turkey supported opposition groups in Syria as a means to weaken Assad’s control, it is now backing a political movement in Yemen that seeks to challenge the status quo, which has been dominated by forces tied to both the Yemeni government and Houthi rebels. By supporting this movement, Turkey seeks to undermine entrenched political powers in Yemen and create a more favorable political environment for its influence to grow.

Shifting Power Dynamics in Yemen: Turkey as a Regional Player

Turkey’s strategy in Yemen, like its actions in Syria, revolves around the idea of strategic positioning and proactive engagement in the region. While Yemen may seem distant from Turkey’s core interests, it holds geopolitical significance in the broader Red Sea and Horn of Africa region, both of which are pivotal to Turkey’s maritime and trade ambitions. Yemen’s proximity to critical maritime chokepoints—such as the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, a key passage for global trade—offers Turkey a chance to extend its influence across the Arabian Peninsula and enhance its regional standing.

Moreover, Turkey’s support for the “Change and Liberation Movement” appears to be a deliberate attempt to weaken the influence of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, two key players in the ongoing conflict in Yemen. Turkey, having grown increasingly at odds with these Gulf powers over their support for opposing forces in the region, may be positioning itself as a counterbalance to their influence. This reflects the same pattern observed in Syria, where Turkey’s backing of Syrian opposition forces aimed at diminishing Iranian and Russian control in Damascus and influencing the eventual settlement of the Syrian war on terms more favorable to Ankara’s strategic priorities.

The Turkish government’s endorsement of non-state actors like the “Change and Liberation Movement” provides an opening for Turkey’s soft power in Yemen. Much as it did with groups opposing Assad, Turkey can build alliances with local actors who are disillusioned with the existing power structures. These movements, especially those that claim to champion reforms such as social justice, the rule of law, and the protection of rights, are a direct challenge to the entrenched elites, which is a situation Turkey can exploit to further its influence.

The Role of Ahmed al-Sharaa and the Syrian Parallel

A notable aspect of the Turkish strategy in both Syria and Yemen is its support for figures like Ahmed al-Sharaa, Syria’s new President and a key figure in the movement. Al-Sharaa’s relationship with Turkey, particularly his support for the opposition in Syria and the broader Syrian Arab Spring narrative, mirrors a broader pattern in which Turkey backs individuals or factions with the potential to undermine the status quo and create a new political reality. In Syria, Turkey’s endorsement of anti-Assad figures like al-Sharaa was a means to create fractures within the Assad regime and strengthen its own hand in any future political settlement. Similarly, Turkey’s support for al-Nahdi’s Yemeni movement might serve to fracture the existing political alignments in Yemen and pave the way for Turkey to shape a post-conflict settlement that favors its interests.

The Turkish government’s long-standing support for Islamist and opposition movements in the region has also shaped its view of figures like al-Sharaa as part of a larger political realignment. Just as Turkey helped to facilitate the rise of political Islam in Syria as a counterweight to Assad’s secular government, its support for al-Nahdi and his movement in Yemen could be seen as part of its broader Islamist foreign policy—aimed at challenging the entrenched secular Arab regimes and promoting political Islam as a force for political change.

A Balancing Act: Turkey’s Challenges and Risks

However, Turkey’s strategy in both Yemen and Syria is not without its risks. In Syria, its support for opposition groups has occasionally led to tensions with local populations, especially when those groups have engaged in behavior perceived as authoritarian or violent. Similarly, in Yemen, Turkey’s embrace of former militants, like al-Nahdi, could alienate key local and international stakeholders. These risks will be compounded by the complexity of Yemen’s own internal divisions, where both local tribal loyalties and foreign involvement complicate efforts to foster a cohesive, stable political order.

Moreover, Turkey’s increasing support for opposition movements in Yemen, including its backing of al-Nahdi’s political faction, may strain its relationship with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, both of which have significant interests in Yemen’s future. These Gulf powers have historically been aligned with the Yemeni government and have supported military interventions in the region. Any Turkish attempt to bolster anti-government factions or sway the political balance could lead to regional confrontation, especially as Turkey’s influence continues to grow in the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

Shaping the Future of Yemen and Beyond

Turkey’s support for the “Change and Liberation Movement” in Yemen reflects a broader regional strategy that seeks to shape the political landscape of the Middle East and North Africa. By backing non-state actors and opposition movements, Turkey aims to undermine established political orders, disrupt Iranian and Gulf Arab dominance, and promote its own geopolitical interests. This approach mirrors Turkey’s efforts in Syria, where it sought to destabilize the Assad regime by backing diverse opposition factions. In both cases, Turkey is positioning itself as a key player in reshaping the regional balance.

However, the risks involved—particularly the potential for alienating key regional actors like Saudi Arabia and the UAE—mean that Turkey must navigate these interventions carefully. Whether its approach will succeed in Yemen, as it has in parts of Syria, will depend on Turkey’s ability to form strategic alliances with local actors and build a new political order that aligns with its long-term regional goals.

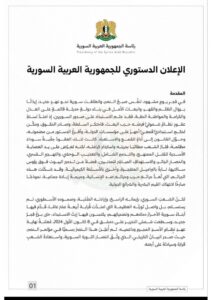

The Syrian Constitutional Declaration, as recently unveiled, has ignited growing alarm among legal and security analysts who see in its structure a potential return to authoritarianism—this time cloaked in religious legitimacy. [40] While framed as a stepping stone toward national reconstruction and post-conflict governance, the declaration exhibits clear signs of ideological exclusivity, centralization of power, and systemic disregard for minority protections. These elements suggest not a break from the legacy of the Assad regime, but a transformation into a more volatile and theocratic model of governance.

The Rise of Salafi Theocracy and Sectarian Exclusion

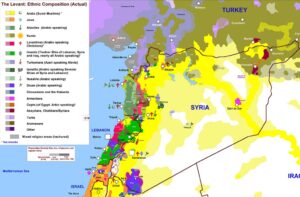

At the core of the concerns is the declaration’s pronounced Salafi-Islamic orientation. The omission of constitutional safeguards for Syria’s rich mosaic of ethnic and religious communities—including Alawites, Christians, Druze, Kurds, and moderate Sunni Muslims—raises red flags about the trajectory of the future state. Analysts warn that this ideological pivot is not merely rhetorical but foundational, aimed at reconfiguring the state’s identity in a way that excludes longstanding populations and flirts with sectarian authoritarianism.

Such an exclusionary model threatens to deepen the very cleavages that fueled the Syrian civil war. The lack of provisions for pluralistic governance and minority rights is interpreted by many as legitimizing a state in which only one religious identity—Sunni Islam of the Salafi strain—is deemed politically viable. This ideological uniformity risks institutionalizing systemic discrimination and provoking further sectarian backlash. The historical precedent is clear: states that define themselves narrowly along religious lines often face internal resistance, splintering, or insurgency—particularly when the definition of citizenship is conditioned on faith.

Power Centralization: A Blueprint for Tyranny

Another grave concern lies in the excessive concentration of executive power. The declaration affords sweeping authority to the president, leaving the other branches of government—legislative and judiciary—functionally subordinate or undefined. Legal experts emphasize that such consolidation of power is inherently destabilizing and undermines any claims to democratic transition. Without robust checks and balances, Syria risks substituting one-man rule under Bashar al-Assad with another form of autocracy under a religious veneer.

A durable transition requires more than symbolic leadership change; it demands an institutional transformation that constrains power and promotes accountability. The absence of a clear separation of powers, coupled with the lack of a bill of rights, opens the door to executive overreach, political repression, and the erosion of civil liberties. In the long run, this imbalance is likely to generate public discontent and delegitimize the very transitional process it aims to initiate.

Political Legitimacy in Question

Beyond structural and ideological concerns, the declaration’s political legitimacy is also in doubt. The involvement of figures associated with extremist factions and the exclusion of diverse political voices further alienate key segments of Syrian society. For a post-war government to succeed, it must foster inclusion, reconciliation, and national unity. Instead, the current framework exacerbates divisions and consolidates power in the hands of a narrow ideological leadership.

Such a framework is especially vulnerable to external manipulation. Regional powers—each with their own strategic agendas—could exploit these fissures to exert influence, fragment sovereignty, or escalate proxy conflicts. In the absence of consensus-driven governance, Syria becomes a battleground not just for domestic interests but for competing regional visions.

The Risk of Renewed Conflict

Perhaps the most dangerous consequence of the declaration’s current form is the increased risk of renewed civil conflict. By sidelining minorities and entrenching a rigid ideological order, the declaration sets the stage for resistance, rebellion, and foreign intervention. A transition that alienates broad swathes of society, instead of integrating them, is unlikely to hold. As competing factions realize their exclusion, armed confrontation may once again appear to be the only viable path to political expression.

This prospect is not theoretical. Similar political configurations elsewhere have rapidly collapsed under the weight of exclusionary governance and sectarian violence. In such environments, fragile peace is illusory and often temporary, giving way to more violent and entrenched cycles of instability.

A Faulty Foundation for a Fragile State

The Syrian Constitutional Declaration, in its current state, offers neither the legal foundation for a democratic transition nor the political framework necessary for national unity. It is ideologically rigid, structurally authoritarian, and politically exclusionary. Instead of serving as a beacon for reform, it risks becoming a constitutional scaffold for a new kind of dictatorship—one whose legitimacy is derived not from the people, but from a narrow ideological doctrine.

Unless the declaration is thoroughly revised to reflect constitutional pluralism, minority protections, and institutional accountability, Syria may find itself slipping from one form of tyranny into another—less secular, perhaps, but no less oppressive or dangerous. The road to peace must be paved with justice, inclusion, and the rule of law. Anything less courts disaster.

If the model embedded in the Syrian Constitutional Declaration—marked by religious exclusivity, centralized authority, and ideological rigidity—is replicated by Yemen’s newly formed Changing and Liberation Movement with the support of Turkey, the consequences for Yemen’s already fractured political landscape could be far-reaching and destabilizing. Such a replication would not only reshape Yemen’s future governance structure but also entrench a regional trend in which transitional movements are transformed into ideological vehicles for proxy influence, leading to a dangerous cycle of exclusion, conflict, and authoritarianism.

The Perils of Ideological Export in a Fragmented State

Yemen, like Syria, is a country defined by deep ethnic, tribal, and sectarian diversity. Any political model that fails to incorporate this complexity risks intensifying divisions rather than healing them. If the Change and Liberation Movement—headed by a figure with a militant past such as Abu Omar al-Nahdi—mirrors the Syrian model by adopting an overtly religious framework, particularly one aligned with Salafi-jihadist underpinnings, it will alienate broad segments of Yemeni society, including the Houthis, southern separatists, moderate Islamists, secular nationalists, and tribal power structures.

Turkey’s involvement, if consistent with its ideological projection in northern Syria, will likely entail the empowerment of Islamist-oriented political currents sympathetic to Ankara’s vision of Sunni political ascendancy. This model, already visible in parts of Syria, privileges ideological loyalty over inclusive governance, and political expedience over legal and institutional development. Imported into Yemen, it could lead to the marginalization of non-aligned factions, thereby intensifying resistance and increasing the risk of renewed civil war, even after any formal political settlement.

Institutional Consequences and the Erosion of National Sovereignty

The replication of a top-down, president-centric model under the pretense of “reform” or “liberation” could erode any nascent institutions built since the outbreak of Yemen’s conflict. The promise of justice and efficiency—two of the stated goals of the Change and Liberation Movement—cannot be realized under a political framework that centralizes power without mechanisms for accountability, transparency, or pluralistic representation. Instead, such a system is prone to co-optation by foreign interests and vulnerable to internal fragmentation.

Turkey’s strategic objectives in Yemen, as in Syria, are unlikely to center on Yemen’s sovereignty or democratic transition per se. Rather, the goal would be to establish a loyal ideological and military foothold that serves Ankara’s broader regional ambitions—particularly in counterbalancing Iran and the UAE, both of which maintain significant influence in Yemen. If Turkey’s assistance empowers a religious-political authority modeled after its Syrian allies, Yemen could witness the creation of a parallel governing structure that competes with, rather than complements, any internationally recognized transitional authority.

The Threat to Social Cohesion and Intercommunal Balance

The religious homogeneity embedded in the Syrian model—where Salafi interpretations dominate legal and societal structures—would be deeply incompatible with Yemen’s pluralist realities. From the Zaidi-dominated north to the Sufi traditions in the south, Yemen’s religious and cultural tapestry cannot be forcibly molded into a singular ideological vision without igniting new societal fault lines. Any movement that does not account for these distinctions risks replicating the very tyranny it claims to oppose.

Moreover, Abu Omar al-Nahdi’s past affiliation with al-Qaeda, despite his later disavowal, casts a long shadow over the movement’s credibility. If Turkey seeks to use this movement as a counterweight to Iran-backed forces, it may inadvertently empower actors who retain radical inclinations, thus complicating counterterrorism efforts and undermining regional security. This scenario could create friction not only with other Gulf states but also with Western stakeholders committed to combating extremism in Yemen.

Strategic Implications and the Risk of Proxy Entrenchment

At a strategic level, the emergence of a Syria-modeled regime in Yemen under Turkish patronage would accelerate the transformation of Yemen into a theater of intense regional rivalry. The country is already plagued by competing visions—Iranian-backed revolutionary governance through the Houthis, Emirati-supported separatism in the south, and Saudi efforts to preserve a unified but pliable Yemen. A Turkish-sponsored Islamist entity would not only add another axis to this struggle but also reduce the likelihood of meaningful national reconciliation.

Rather than moving toward peace, Yemen could become the stage for prolonged political fragmentation, where every external actor props up its own ideological ally, rendering the concept of a unified state ever more elusive. The practical result of such a development would be a de facto partition—perhaps not declared formally, but real in terms of governance, security, and economic control.

A Mirror with a Dark Reflection

If the Change and Liberation Movement adopts the Syrian model under Turkish influence, Yemen is likely to experience a deeper entrenchment of sectarianism, institutional fragility, and foreign dependence. Far from being a force for liberation, such a movement could become the nucleus of a new form of authoritarianism, legitimized by religion and enabled by geopolitical calculus. The path to peace and reconstruction in Yemen lies not in replicating external ideological blueprints but in cultivating an indigenous, inclusive, and accountable political process that acknowledges Yemen’s unique history and multifaceted identity. Anything less will invite disaster.

The emergence of two former al-Qaeda-linked figures in leadership roles within transitional political movements—Abu Omar al-Nahdi in Yemen’s Changing and Liberation Movement, and Ahmed al-Sharaa in Syria’s post-Assad opposition—raises compelling questions about patterns, intent, and strategy. While it may appear coincidental on the surface, the recurrence of such figures in positions of influence, particularly within spheres shaped by Turkish geopolitical maneuvering, is more plausibly a product of a calculated strategy than happenstance. This pattern reflects Ankara’s broader regional doctrine of selectively empowering ideologically compatible actors who possess both local legitimacy and operational experience, especially in territories where Iran’s influence is strong and Western engagement has waned.

Strategic Cooptation of Former Militants

Turkey’s pragmatic engagement with former jihadist or militant elements is not without precedent. Ankara’s posture toward various factions in northern Syria, including those with controversial origins or affiliations, has been grounded in its dual objectives: curbing Kurdish autonomy along its borders and projecting Sunni political authority into post-conflict spaces. By co-opting figures like al-Sharaa and al-Nahdi—both of whom have shed their militant guises and repositioned themselves as political reformers—Turkey is effectively engaging in ideological laundering. These figures, though formerly associated with extremist networks, now offer the benefit of deep local networks, combat credentials, and symbolic narratives of transformation, which Turkey harnesses to legitimize its influence while countering the dominance of Iranian-backed or secular-nationalist actors.

This approach allows Turkey to insert itself into the vacuum left by disengaged Western powers and to present itself as the indispensable patron of “authentic” Sunni-led political revival movements. These actors may be controversial abroad, but in Turkey’s calculus, they are tools to shift the power balance, particularly in contested arenas like northern Syria and southern Yemen.

Exploiting Iran’s Overextension and Western Ambivalence

Iran’s deep entanglement in both Syria and Yemen has bred resentment among large sectors of the local populations, particularly Sunnis who feel politically disenfranchised and culturally marginalized. Turkey exploits these dynamics by supporting figures and movements that frame themselves as nationalistic reformers but resonate with Sunni-majority constituencies. The West, preoccupied with internal challenges and unwilling to commit robust diplomatic or military resources to these conflicts, has effectively created a permissive environment in which Turkey’s agile and opportunistic policy flourishes.

Ankara’s strategy, therefore, is not solely about confronting Iran—it is also about exploiting its sectarian excesses. In Syria, Iran’s support for Assad alienated much of the population. In Yemen, Iran’s backing of the Houthis created an opening for rival movements to portray themselves as the protectors of Yemeni identity and Sunni values. Turkey has moved into that space with ideological dexterity, positioning itself as a liberator from both Iranian hegemony and Western negligence.

Rehabilitating the Narrative of Extremism

The Turkish strategy also serves to subtly rehabilitate the narrative around former jihadist figures. By investing in their political evolution, Ankara dilutes the global stigma associated with these individuals, transforming them into nationalist heroes or revolutionary reformers in domestic discourse. This reframing helps Turkey deny Western accusations of sponsoring radicalism while simultaneously integrating battle-hardened cadres into a new regional order that aligns with Ankara’s interests.

However, this tactic is not without significant risks. The reliance on former extremist actors may provide short-term gains in influence and military discipline, but it carries the long-term danger of legitimizing exclusionary ideologies. If these movements, once in power, suppress minorities or establish governance structures rooted in religious dogma rather than civic inclusion, the result could be new cycles of insurgency and external intervention—ironically mirroring the very instability Ankara claims to counter.

A Calculated Gamble

The ascent of former al-Qaeda affiliates to political leadership under Turkish auspices is no accident. It reflects a bold, ideologically informed strategy designed to recalibrate regional dynamics, fill power vacuums left by the West, and marginalize Iranian proxies. While this approach has thus far yielded strategic leverage and enhanced Ankara’s regional clout, it is a high-stakes gamble. The long-term viability of these actors as instruments of stability or legitimacy is far from assured. If their governance models replicate the authoritarian or sectarian excesses of their predecessors, Turkey’s short-term success may ultimately sow the seeds of deeper fragmentation and conflict in both Yemen and Syria.

If Turkey succeeds in cultivating a Yemen-Syria axis composed of ideologically aligned, fragile but cooperative movements, the region may witness the emergence of a new strategic paradigm—one shaped not by the conventional architecture of strong nation-states, but by semi-institutionalized political actors with Islamist orientations and close ties to Ankara. This axis would reflect Turkey’s evolving approach to post-Arab Spring realignments: backing pliable, populist movements that can provide regional leverage while remaining dependent on Turkish political and economic patronage. The implications of such a development would reverberate far beyond the borders of Yemen and Syria, with consequences for regional alliances, ideological narratives, and the balance of power in the broader Middle East.

The Anatomy of a Fragile Islamist Axis

At the core of such an axis would be a shared ideological framework loosely rooted in Sunni Islamist populism, national liberation rhetoric, and anti-Iranian resistance. Both the Changing and Liberation Movement in Yemen and the post-Assad Syrian opposition (under figures like Ahmed al-Sharaa) are attempting to fuse Islamist roots with nationalist aspirations, presenting themselves as reformist alternatives to both Shi’a-dominated regimes and corrupt secular elites.

A Turkey-supported axis would likely emphasize several unifying features:

Religious Legitimacy and Moral Governance: These actors would portray themselves as clean, morally grounded alternatives to both the Assad regime and the Houthi-Saleh networks, contrasting their movements with what they characterize as foreign-imposed tyranny or sectarian oppression.

Anti-Iranian and Anti-Western Rhetoric: While strategically benefiting from certain Western institutions, this axis may cultivate narratives of self-determination that reject both Iranian expansionism and what they see as Western complicity in maintaining the regional status quo.

Dependency on Turkey for Political, Economic, and Diplomatic Lifelines: These movements, lacking strong internal institutions, would lean heavily on Turkish investment, training, and diplomatic shielding at the international level.

Non-State or Semi-State Cooperation Models: In the absence of consolidated state power, cooperation would be fostered through military coordination, ideological exchanges, and mutual legitimization through symbolic summits and joint declarations.

Models of Cooperation and Mutual Reinforcement

The axis, though inherently fragile, could be designed to compensate for institutional weaknesses through transnational solidarity. Leaders like al-Nahdi and al-Sharaa could share resources, establish intelligence coordination mechanisms to combat rival factions (particularly those supported by Iran or the UAE), and create joint humanitarian fronts that leverage Islamic charitable networks to gain popular support.

In the digital domain, the movements might collaborate on media narratives, using Turkish-backed outlets to amplify their legitimacy and frame their opponents as agents of foreign subjugation.

Educational and religious institutions could also serve as soft power tools, embedding a shared worldview among the younger generation.

Internationally, they would benefit from Turkey’s lobbying power in multilateral forums, especially in the Islamic world, where Ankara has steadily positioned itself as a champion of disenfranchised Sunnis. Joint appeals to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), partnerships with Qatari-backed NGOs, and rhetorical alignment with causes like Palestinian liberation would help burnish their credentials on the global stage.

Turkey’s Strategic Dividend

For Turkey, the emergence of a compliant Yemen-Syria axis would be a geopolitical masterstroke. It would offer:

Strategic Depth: Anchoring influence from the Levant to the Arabian Peninsula would provide Turkey with unprecedented maneuverability in Gulf politics, the Red Sea corridor, and along Iran’s southern and western flanks.

Containment of Iranian Influence: These proxy entities would act as ideological and political counterweights to Tehran’s Houthi and Assad-aligned forces, effectively boxing in Iran’s regional project.

Leverage Over the West: As the patron of movements perceived as “lesser evils” compared to more radical or Iranian-aligned factions, Turkey could position itself as an indispensable intermediary in conflict resolution efforts.

Soft Empire without Formal Annexation: Through strategic partnerships, Turkey could project power and ideology without the burdens of direct governance—allowing for expansion of influence while maintaining plausible deniability.

At Whose Expense?

Such a transformation would significantly disrupt the strategic ambitions of multiple actors:

Iran would lose ground in both Yemen and Syria, undermining its vision of a contiguous axis of influence stretching from Tehran to the Mediterranean.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE would find themselves increasingly isolated, as Turkey’s Sunni populist movements challenge their more hierarchical, state-centric models of regional order.

The United States and Europe would be further marginalized, particularly if these movements fuel anti-Western sentiment or erode Western-backed transitional frameworks.

Israel may face heightened risks from ideologically Islamist governments with ties to Hamas-style rhetoric, even if actual military threats remain diffuse.

A Fractured Order with a Coherent Vision

If Turkey manages to consolidate a Yemen-Syria Islamist axis under its tutelage, it will have achieved a significant reconfiguration of post-Arab Spring geopolitics. Fragile though these movements may be, their shared narrative, external sponsorship, and ability to co-opt local grievances could allow them to punch above their institutional weight. For Turkey, this axis is not merely about ideological solidarity—it is a pragmatic, flexible strategy to build influence, compensate for conventional military and economic limitations, and redefine the regional order in its own image. Yet this order, while coherent in vision, would be fractured in execution—vulnerable to internal dissent, external backlash, and the inherent instability of movements born from the ashes of war.

If Turkey succeeds in constructing a functional axis between ideologically aligned movements in Yemen and Syria, it would represent not merely a regional tactical gain, but a meaningful step toward reviving Ankara’s long-cherished vision of neo-Ottoman influence. This strategy, though dressed in the language of moral diplomacy and anti-imperial solidarity, serves a deeper ambition: reshaping the post-colonial Middle East into a sphere where Turkish cultural, economic, and political power reignites its historical centrality. Yet, to realize this vision, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan must walk a tightrope—leveraging foreign influence to consolidate geopolitical stature abroad while managing an increasingly fragile domestic political environment.

Turkey’s Strategic Gains: Toward a Neo-Ottoman Footprint

The integration of Syria and Yemen into a soft alliance of Turkish-aligned, Islamist-leaning, non-state actors would serve as a geopolitical multiplier for Ankara. Historically, both regions were once integral parts of the Ottoman Empire, and their symbolic reclamation—even if informal—plays directly into Erdoğan’s neo-Ottoman narrative, which positions Turkey not just as a state among others, but as the natural leader of the Sunni Muslim world.

Such an axis would offer several critical advantages:

With influence stretching from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, Turkey would gain de facto control over vital chokepoints for global trade, maritime navigation, and energy flow—areas that are currently contested by Saudi, Emirati, and Iranian ambitions.

By sponsoring movements that blend Islamic populism with national liberation rhetoric, Turkey can position itself as an alternative to both the Iranian revolutionary model and the Gulf’s technocratic autocracies. These narratives resonate with disenfranchised youth and marginalized Sunni populations, creating fertile ground for Turkish soft power expansion.

Unlike direct military occupation or costly reconstruction, supporting compliant movements allows Ankara to shape regional dynamics while minimizing financial burdens and avoiding direct confrontation with global powers. The result is a hybrid empire—less a territorially defined entity, more a network of dependent ideological and political vassals.

The rise of Turkish-aligned Islamist actors would undermine Iranian strategic corridors and displace Emirati-backed militias. Simultaneously, this weakens Western influence in post-war transition processes, especially in areas where the U.S. and EU have struggled to build lasting political partnerships.

Balancing Foreign Ambitions with Domestic Instability

However, this external expansion comes at a time when Erdoğan faces serious domestic constraints. The arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, a popular opposition figure, has already triggered mass protests, with demonstrators denouncing authoritarian overreach and judicial politicization. Coupled with a stagnating economy, inflationary pressures, and growing discontent among both secularists and moderate Islamists, Erdoğan’s internal legitimacy is increasingly tenuous.

To balance this contradiction, the Turkish president will likely employ a multi-pronged approach:

Success abroad—particularly framed as a triumph over imperialism, terrorism, or foreign conspiracies—serves as a distraction from internal dissent. Ankara may frame its Yemen-Syria engagements as moral obligations or national security imperatives, rallying nationalist sentiment to suppress opposition narratives.

Turkey will likely avoid overcommitting material resources. Support for these movements may be channeled through intelligence coordination, media networks, NGO fronts, and targeted aid rather than large-scale troop deployments or economic reconstruction schemes. This low-cost model reduces exposure to backlash at home.

By supporting movements that align with Erdoğan’s religious and cultural worldview, Ankara can reinforce its identity-based legitimacy among conservative voters. This softens the blow of economic hardship with appeals to religious destiny and national pride, especially in Anatolian heartlands.

Domestically, Erdoğan may continue suppressing high-profile opposition figures while offering calibrated economic or social incentives to mitigate mass unrest. The goal is to exhaust the protest energy without appearing weak.

The Neo-Ottoman Tradeoff

The neo-Ottoman project, in its current iteration, is not about formal colonization or annexation. It is about symbolic revival and strategic depth—asserting Turkey’s role as the cultural and political center of the Sunni Muslim world. But the sustainability of this model hinges on Erdoğan’s ability to prevent blowback: externally, from powers like Iran, Russia, and even the U.S., and internally, from a citizenry increasingly skeptical of imperial overreach and economic stagnation.

If the public begins to perceive foreign adventures as draining or as smokescreens for domestic repression, Erdoğan’s balancing act may falter. Conversely, if he succeeds in crafting a narrative of revival, justice, and pan-Islamic leadership—while maintaining enough domestic control—Turkey may emerge as the nucleus of a new regional order. In that sense, the Yemen-Syria axis is both a testing ground and a proof of concept for the wider neo-Ottoman doctrine. Whether it becomes a durable pillar of Turkish influence or collapses under its own contradictions will depend on Erdoğan’s skill in fusing ideological ambition with pragmatic statecraft.

The consolidation of a Turkish-backed axis between Yemen and Syria, now under the leadership of President Ahmed Al-Sharaa and the Syrian Unity Government, marks the emergence of a new ideological and geopolitical order in the Middle East—one in which fragile, conflict-scarred states are restructured under fundamentalist regimes closely aligned with Ankara’s strategic ambitions. With the Syrian Constitutional Declaration already implemented and the concerns over its theocratic leanings manifesting in daily governance, this regional transformation has moved from theory to practice. The alliance is no longer a hypothetical alignment of interests; it is a functional axis with shared doctrine, shared vulnerabilities, and expanding ambitions.

Kurdish Autonomy as a Casualty of the Axis

With the Syrian Unity Government fully operational and increasingly consolidating authority through institutions favoring a Sunni fundamentalist ideology, the position of Kurdish communities in northeast Syria has become more precarious than ever. The initial marginalization of Kurdish representation in the new political framework has escalated into active suppression, with reports of displacement, restrictions on cultural expression, and the closing of local councils that had previously operated with semi-autonomous authority.

This model of religious exclusion, already observed in Syria, provides a blueprint for the newly formed “Changing and Liberation Movement” in Yemen, which is drawing heavily from the same ideological reservoir. If this Yemeni entity gains political traction under Turkish patronage, it will likely replicate the Syrian model—leveraging revolutionary legitimacy to impose a majoritarian religious order that systematically excludes minorities, secular actors, and competing national visions, including those of the southern independence movements and tribal federalists.

In Turkey, this bolsters the government’s ongoing campaign against Kurdish elements. The rise of ideologically compatible regimes in Syria and Yemen gives Ankara strategic depth, allowing it to coordinate cross-border pressure on Kurdish actors and justify further militarized policies at home. Domestic crackdowns can now be framed not merely as internal security measures but as part of a broader “regional stabilization” effort against separatism and terrorism.

Iraq: The Next Domino in an Anti-Iran Campaign

As Turkey strengthens its influence through ideological proxies and allied leadership in both Syria and Yemen, attention will naturally turn toward Iraq—particularly the Sunni-majority regions of Anbar, Nineveh, and Salahuddin. With Iranian-backed militias entrenched in Baghdad’s power structure, Turkey sees an opportunity to build a parallel network of Sunni actors to counterbalance Tehran’s grip.

The emergence of a Sunni Islamist axis between Damascus and Seiyun provides a compelling narrative to mobilize former insurgent networks, tribal leaders, and disenfranchised populations in Iraq’s west. The goal is not only to challenge Iranian influence but to integrate Iraq’s Sunnis into a wider Turkish-led framework that promises both ideological resonance and material support.

This would place the Kurdistan Region of Iraq in an increasingly vulnerable position. As Turkey expands its presence—militarily through bases, politically through patronage of Sunni groups, and economically via infrastructure deals—Erbil may find itself squeezed between an emboldened Turkey and an antagonistic Iran. Its political survival may depend on navigating an impossible middle ground between these rival hegemonies.

The New Brotherhood: A Return by Another Name

The ideologies guiding both the Syrian Unity Government and the nascent Yemeni movement reflect a fusion of Muslim Brotherhood thought and battlefield pragmatism. The Brotherhood’s emphasis on popular mobilization, religious governance, and opposition to both Western liberalism and Shi’a theocracy has found fertile ground in societies wrecked by war and foreign intervention.

But unlike earlier Brotherhood experiments in Egypt and Tunisia, these new regimes are not moderated by democratic pretensions or constitutional pluralism. They are born in militarized conditions, legitimized by revolutionary mythologies, and stabilized by external patrons—in this case, Turkey. The governance model emerging in Syria, for instance, is marked by an aggressive centralization of power, the integration of armed factions into state institutions, and the systematic marginalization of minorities and secular groups.

If the Yemeni iteration follows suit, the region will witness the normalization of Brotherhood-style rule that is neither democratic nor accountable, but deeply ideological and resilient through cross-border alliances. This alignment enhances Turkey’s strategic posture but raises alarm among regional powers such as Egypt, the UAE, and segments of the Saudi establishment, all of whom have actively fought against Brotherhood influence in their own spheres.

Turkey’s Strategic Windfall—And the Growing Risk

For Ankara, the ideological and strategic alignment of Syria and Yemen under friendly, Turkey-backed governments would be a major geopolitical victory. It extends Turkish influence from the Levant to the Arabian Peninsula, bypassing Gulf rivalries and circumventing Iran’s Shi’a arc. It enables Ankara to build a regional identity rooted in a neo-Ottoman vision—one in which Sunni Islamist regimes cooperate politically, militarily, and economically under Turkish guidance.

This axis allows Turkey to:

Project hard and soft power across multiple theaters.

Build ideological legitimacy among Sunni populations.

Export its model of centralized religious governance.

Counterbalance Iranian and Gulf influence in fragile states.

However, this vision is not without its dangers. The expansion of Turkish influence through ideological regimes also invites blowback. Domestically, Erdoğan faces increasing economic unrest and mass protests, particularly following the controversial arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu—a symbol of opposition strength. Balancing this expanding foreign agenda with internal instability will test the limits of Turkish governance.

Moreover, the more Ankara supports regimes that alienate minorities and rule by religious decree, the more it risks international isolation and growing resistance from within these very societies. A Sunni axis that marginalizes Alawites, Shi’a, Kurds, and secular voices is unlikely to produce stability—and more likely to incubate a new cycle of insurgency and foreign intervention.

A Fragile Axis, A Dangerous Gamble

The Syrian Unity Government under President Ahmed Al-Sharaa is already offering a preview of what Turkey’s regional order looks like in practice—centralized, exclusionary, and ideologically rigid. If this model is replicated in Yemen and expanded into Iraq, the Middle East may face a new era of factional competition dressed in religious rhetoric and legitimized by revolutionary populism.

While Turkey stands to gain strategic depth, regional leverage, and ideological alignment, the cost may be mounting instability, suppressed minorities, and a future where today’s fragile alliances become tomorrow’s failed states.

Disrupting the emergence of a Turkey-aligned fundamentalist axis stretching from Syria to Yemen requires an urgent, multidimensional strategy that addresses not only the geopolitical architecture being constructed by Ankara, but also the underlying ideological, institutional, and societal vacuums that are enabling its formation. This axis is not being built in a vacuum; it is the result of strategic neglect, misplaced diplomatic priorities, and the failure of the international community—particularly Western powers—to offer viable alternatives to war-torn and fractured states.

If the region is to avoid a reconfiguration along the lines of a Sunni Islamist belt under Turkish patronage, with consequences ranging from sectarian cleansing to the rollback of hard-won rights and freedoms, then a course correction must begin immediately, rooted in five key domains:

Reclaiming the Political Center in Syria and Yemen

The first step toward disrupting the axis is empowering legitimate political actors who can challenge the monopoly of Islamist factions in the transitional and post-conflict governance structures. In Syria, the international community—especially the U.S. and EU—must stop treating the Syrian Unity Government as a fait accompli. While Al-Sharaa may hold power, recognition and legitimacy should be contingent upon pluralistic reform, constitutional guarantees for minorities, and the demilitarization of governance. Support must be shifted toward independent secular, tribal, and ethnic opposition leaders who were sidelined during the power transition.

In Yemen, the Changing and Liberation Movement must be subjected to scrutiny. It should not be allowed to launder its image through civil political engagement while maintaining the ideological infrastructure inherited from its leader’s extremist past. Civil society, tribal authorities, and local federalist movements—particularly in Hadramaut, Marib, and the south—must be resourced and empowered as counterweights to any new ideological monopolies.

Redrawing the Regional Diplomatic Landscape

A vacuum in strategic diplomacy is what allowed Turkey to step in and create ideological continuity between fragmented Islamist actors. To counterbalance this, regional heavyweights such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the UAE must revitalize their coordination to offer a counter-axis focused on stability, state institutions, and moderation.

Rather than merely reacting to Turkish moves, this coalition must offer tangible alternatives: reconstruction aid tied to constitutional inclusivity, investment in civil governance, and support for independent media and education reforms. The Gulf states must also extend their influence in Yemen and northern Syria not solely through military presence, but by shaping the post-war narratives and offering viable futures to disenfranchised populations.

Strategic Reengagement by the United States

For Washington, the price of disengagement has become clear. In the absence of a sustained U.S. footprint—militarily, diplomatically, and in civil reconstruction—ideologically motivated actors have filled the void. If the U.S. wishes to prevent a fundamentalist reordering of the region, it must rethink its posture in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

This does not require a return to full-scale military operations, but it does demand a robust diplomatic initiative that brings together regional partners, enforces red lines against extremist governance, and conditions aid and recognition on inclusive, representative politics. It also necessitates confronting Turkey where necessary—particularly in forums like NATO—regarding its support for ideological movements with destabilizing regional agendas.

Strengthening and Integrating Kurdish and Minority Voices